Arch

443/646: Architecture and Film

Winter 2014

Brazil (1985)

|

Arch

443/646: Architecture and Film Brazil (1985) |

|

Discussion Questions:

Remember, your images are ABOVE your name.

Please answer the questions below. Use paragraph form. Submit to LEARN. THINGS TO KEEP IN MIND WHEN ANSWERING THESE QUESTIONS: I am looking for general observations about the film and the relationship to any aspect of f/x that we have examined. The images attached to your "words" are to clarify the intention but are not meant to be action specific. PLEASE TIE YOUR ANSWER TO ONE OR MORE OF THE OTHER FILMS THAT WE HAVE VIEWED SO FAR THIS TERM. i.e. how did Renaissance use your word or picture clue to create an effect and how did another film that we have studied this term do this is a similar way. |

x |

|||||

| 1. |   |

||||

Hillary Chang The use of lighting in this film emphasized its futuristic setting and the intensity of certain scenes. Most scenes had some degree of a neon light; computer screens and objects meant to seem hi-tech were brightly backlit, and often entrances and other machinery had lights pinned around them. The unnatural glow and the out of the ordinary placement of these lights led viewers to believe they had an plausible function unknown to our time. Lighting was also used as an indicator of daytime in the film; electronics seemed to govern when it was time to wake up in the morning, turning on the “sun” to wake the protagonist in the morning although at times failing to do so. Electronics and machines played a conflicting role against the protagonist; when the protagonist would become frustrated with machines, lights would begin to flash and alarming sounds would increase the character’s frustration. Similarly, in the film Alphaville, high contrast lighting and unnatural lighting also enhanced its futuristic feel without changing pre-existing sets and props. Lighting in Alphaville chose to use dimly lit scenes to increase the suspicion felt by the detective, drawing focus to the unfamiliar pieces of technology instead of the familiar architectural forms. During scenes with emergencies and chaos, the lighting became high in contrast would begin to strobe; this added to an increase in the noise from the scene’s action as well as moving camera angles made these scenes feel full of action and excitement. In a similar way, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari’s dynamic backdrop sets accentuated exciting scenes, changing the atmosphere of a scene with the aid of sound effects. |

|||||

| 2. |

|

||||

Patrick Cheung The future in Brazil is created through sets and parodies of the ideas of “the future”. It appears as if every set in the film has been built or modified to an extent that looks and feels foreign to the audience, or the people of “the present”. Cars are at scales unfamiliar to us, buildings look like they've been taken straight out of a set of sci-fi sketches, and the machines and products shown in the film are like nothing we've seen before. The occupation of these spaces, and use of these objects by people make us believe that they are in the future. The film also uses parody as a technique to set the present apart from the future. The characters in the film act in such a ridiculous manner that we cannot associate it with our time. In this future, phones require complicated plug-in ports to answer, ordering food from a restaurant requires you to repeat the item number, government processes are complicated to such an extreme that it becomes a joke to us. Simple everyday objects and tasks are turned into things that are unmanageable by the average citizen, presumably because people felt the need to develop where development was not required, for the sake of “advancing” into the future. Such foreign customs, behaviors, and objects, combined with the use of a convincing set, make us believe that these people are not of our time. A similar technique is used in Jacques Tati's Playtime, which was shot entirely on a built environment, and set in a near-future Paris. Buildings and objects in Playtime's Paris look unique from the Paris of the time, the characters interact with their world in a manner unique from Parisians of the time. All these changes in the world are viewed as “enhancements” and “advancements” on our modern world, and so we're lead to believe that the characters do live in the future.

|

|||||

| 3. |   |

||||

Wesley Chu

|

|||||

| 4. |   |

||||

Charlie Gao

|

|||||

| x | 5. |   |

x | ||

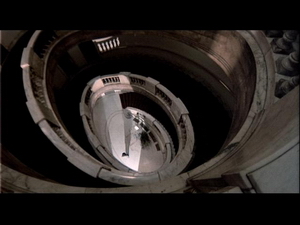

Maighdlyn Hadley Terry Gilliam’s Brazil is set in a fantastical, maximalist dystopian future, dense with people, machinery and excess. This dystopian future is expressed in the film through a language of civic architecture that is crammed and narrow, which poses a stark contrast to the empty, cavernous architecture of the Central Services buildings. The extreme shots from above highlight and exaggerate the hallways and chasm-like stairwells. It gives a sense of endlessness to the architecture – each hall leads to a floor with infinitely more doors leading to more hallways. People are dwarfed in these settings, insignificant and ineffectual in comparison to the massive structure surrounding and confining them. The plot regulates the scale of the architecture – frantic, comic exchanges take place in cramped and convoluted spaces with lots of cluttered extraneous service ducts, pipes and tubes. More sinister, epic scenes take place in very vertical, cavernous spaces – most notably the end, in which Sam Lowry is captured and strapped to a chair on a gangplank in the empty cylindrical cooling tower of a power station, awaiting torture and lobotomy at the hands of his former friend. These extreme views were created through a combination of camera artistry (using a short, wide-angle lens, as is typical for Gilliam) and through just filming in truly impressive spaces; unlike Metropolis’ use of fabricated sets to create a dystopic future, scenes of Brazil were shot on-location all over Europe. “The Information Retrieval torture chamber where Sam is interrogated was shot in a cooling tower at a power station in South London. The stunt men who rescue Sam during his interrogation had to descend a distance of 170 feet to 9-inch wide metal spines 40 feet above the ground for Sam's escape scene.” (David S. Cowen. BRAZIL Frequently Asked Questions). In this scene, the extreme shot from above reinforces Gilliam’s theme of the insignificance of human life in this future Brazil, a world where machinery and bureaucracy reign supreme. Sam Lowry is a cog in the bureaucratic juggernaut, and when he ceases to perform as such, he is taken out of commission like a defective piece of machinery.

|

|||||

| 6. |   |

||||

Kyle Jensen In the film “Brazil” a series of objects were manipulated through deliberate camera techniques, skewing and distorting the subject matter. A wide angle lens was used in the film along with strategically placed objects in the foreground and background, allowing the distortions to add effect to the environment in the film. The technique, also known as perspective distortion, uses axial magnification to distort the edges of the frame while maintaining a less distorted central focus. In “Brazil” the effect is used to produce an unsettling atmosphere in specific shots, for example when the shortcomings of technology and the inefficiencies of an organized government are being captured. These distortions are also used to exaggerate space within the dream state of the main characterʼs mind, making for hugely disproportional alleys with impossibly tall walls around him. The presence of a stern, powerful and dysfunctional government is the main focus in the film. Perspectives showing the elevated position of power that the government agents hold over the people can be seen through the deliberate camera angle capturing its officials, similar to a child looking up at a counter that is too tall for him to see over. This perspective makes the viewer feel small while blurring the complicated equipment on the desk into a distorted, confusing mess. The distortion used emphasizes the officialʼs power over the citizen just as he holds the power over the complicated technologies in front of him, further illustrating political empowerment. I feel that the overall impression of imposing dominance and authority over the citizens was communicated very effectively in a manner that made it simple to grasp. The technologies shown in this film seemed like prototypes. Little to no design was seen to hide or clean up their component parts, resulting in a very clunky and unrefined technological elements. The use of perspective distortion when looking at the technologies added to this untidy and unorganized state of exposed electronics, making the viewer almost dizzy from the presence of all the layered circuits and tubes. The technology was exposed in the film to be faulty as its mistake led to the murder of an innocent man. The disorder and utter chaos of the technologies in use show their inaccuracy and add to the overall absurdity of the societyʼs trust in the systems they are presently using. The distortions also are used to exaggerate personal perspectives of specific surroundings, increasing the charactersʼ emotions and creating unsettling environments. The main character Sam Lowry, played by Jonathan Pryce, uses this exaggerated perspective in his daydream or fantasizing mind sequences to exaggerate the spaces he is inhabiting. Specifically, we see this while he is inhabiting a maze of darkened alleyways in his quest to save the imprisoned damsel in distress. The building structures that frame the darkened alleys are exaggerated, making them look impossibly tall, and the alleys seem to extend to infinity. In addition, a close up of his face where the background and extremities of the shot were extremely distorted added emphasis to the skewed reality that he was experiencing in his mind when in a dream-like state. The specific scene showing the curved walls of the torture chamber, a retrofitted cooling tower silo, was the most powerful exaggeration as the shape of the room itself added to the overall distortion and made an already disturbing environment, even more grotesque. Overall, the distortion of his mental state shows his disconnect to his surroundings as he finally drifts into a coma, allowing him to live through the alternate reality in his mind. This exaggeration of space using perspective distortion was also seen in the film “Play Time” by exaggerating the scale of buildingsʼ interior dimensions, making them look taller, hallways longer and working cubicles more plentiful. In this film the disproportionate perspective increased the expansive feeling of modernist architecture, making the viewer uncomfortable in the space as the observer feels small and exposed. Although a less sinister aspect is applied in this case, a similar illusion of space is used to create an overall uncomfortable sensation for both the character and the viewer. Understanding perspective distortion reference |

|||||

| 7. |   |

||||

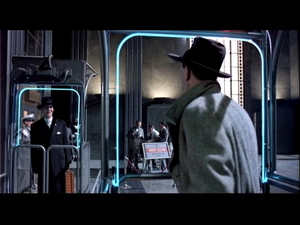

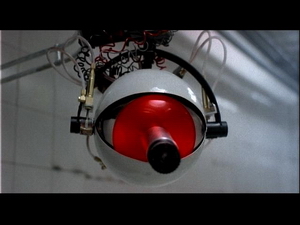

Dan Kwak Much like any other seemingly fragile appearance of technology in Brazil, the modes of security control are also represented impotent in a sense. Gilliam’s satirical illustration of dystopian technology leaks in this symbolic representation. For example, the scene where Sam encounters Jack during the check-up point illustrates a thin-metal gate with a cheesy, cheap-looking neon-light tube. This security structure seems easily destructible if anyone were to try. Aren’t those metal gates for impeding the invalid person if he supposes a danger? In fact, as if to juxtapose this strangeness, the scene carries briefly to the view of the sideline of the gates: the screening computer, security officers and so on. It concludes, not so much is the security control as means of a physical prevention or defence against the offensive; its sheer purpose is to read the person’s identity. The individual identity and personal information are the essential materials that the authority requires for its status of security. Likewise, a person’s status in the society, through his / her personal information, establishes his / her means of security within that society – in this case, Gilliam’s information-technology driven, bureaucratic society. Hence, on the basis of his status quo and identity in the society as a government employee, Sam’s security is guaranteed but also constantly checked. Gilliam represents this fragility of personal identity by his decorative illustration of such a fragile, annoying appearance of technology and in this case, in the form of security control. Another good example is when Jill is constantly monitored by this insect-like, revolving camera robot that annoyingly sweeps around her. She punches it down in her built frustration. Meanwhile the security officer, who was controlling the robot, is only a few feet away from her. Or when Sam and Jill are both surrounded by heavy guards in the lobby, Sam’s flashy identity instantly halts the guards; eventually this authoritative power of an identity is what leads Sam to his death. The satirical approach and the director’s means of representation through the image of security control is quite similar to that of Alphaville, where the visual appearance of a dystopian element is intentionally “dumbed” down in order to establish the director’s satire. For example, Godard implies his satirical view of dystopian technology as nothing more than a voice without a physical entity. Both Godard and Gilliam explore the relationship between the authoritative society and the individual where Godard implores the technology as basis, and Gilliam does so with the personal identity. Gilliam also involves technology, but it all boils down to the question of information and personal identity. Importantly, both directors (if this were to be regarded as a narrative technique in its own sense) represent the appearance of a dystopian element, i.e. security control in Brazil, as ridiculously humble and fragile in order to build their intended satire. |

|||||

| 8. |   |

||||

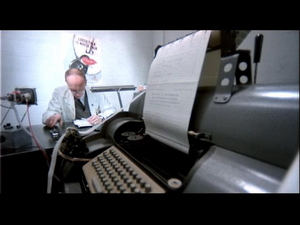

Milos Mladenovic Technology is obviously a strong theme in Brazil. Obtrusive ducts seem to be hanging in every scene, someone is glued to a TV screen in almost every other scene, and even many changes of scenes and transitions are connected by TV screens. The oscillating ducts which give off a breathing noise render the city as a mechanical, living machine that is everywhere and is always on. This living city is apparently powered by pneumatic tubes, typewriters, lenses, and the omnipresent ducts. From the onset of the film it appears to be everywhere, however, unlike a film like Bladerunner, the technology in this film is not extraordinary in that it represents a futuristic world that is more capable than ours today. Rather, the technology that clutters the scenes of Brazil appears clunky, outdated, and not dissimilar to the technology that existed in the 1980s. It seems to suggest that it's an alternate version of the present rather than a dystopic future of our own universe. Further, the technology in the film appears in many cases clumsy and ineffective, especially when people attempt to interact with it. For example, when Sam's office neighbor asks him for help with his "broken" computer, Sam shows him that he has simply yet to turn it on. Similarly, the technology that is so pervasive in the film is proved to be incredibly unreliable and incapable when a seemingly simple jammed bug requires an abundant amount of time and resources to fix due to the organized and centralized institutions dealing with them. Even at the beginning of the film, Sam's apartment causes him to drink sugar instead of tea and have soggy toast as breakfast. In many cases, as well, when these technological systems fail or malfunction, they provide a comedic effect not only in themselves but also in the human interactions that have to take place because of them. For example, when Sam must deliver the refund cheque to a woman after her husband dies, he takes the opportunity to explain that it is out of the ordinary that he has to personally deliver the cheque which normally goes automatically through the automated central services. In other cases, the people in this film try to appear ignorant to the clumsiness or pervasiveness of technology in their world, as in the dinner scene when the women with plastic surgery attempt in vain to continue their meal while ducts and malfunctioning technology are literally physically obstructing them. In the end, the technology plays a somewhat paradoxical role: it paints the sci-fi picture of a city in which the State is omnipresent (connected to every part of the city by ductwork and TV screens, even connected to every scene by means of transitions that utilize the TV screen), but also critiques the effectiveness of that technology in its clumsiness itself and in the dehumanized interactions of people with machines and people with people that it causes.

|

|||||

9. |

|

||||

Arturo Rivera In Brazil, Terry Gilliam presents a futuristic and technologically-advanced society in which government bureaucracy takes more relevance than the very own people that constitute it. Within the first minutes of the film, it becomes very apparent that the tone of the movie is very pessimistic, with a very desaturated color palette and industrial settings, depicting modernity as if it represented the death of the human soul and spirituality, leaving nothing but mindless and repetitive work to fill the days of the people. Almost all of the action in the film takes place in interior spaces, alternating between the government offices and the apartments in which the people dwell, both designed in a “modernism-gone-wrong” fashion. These spaces are filled with technological gadgets and advanced gizmos, but what makes them really stand out is the fact that they rely heavily on the use of artificial lightning as the main source of illumination; this in turn produces a very specific atmosphere, almost as if those spaces were prisons instead. On the note, there is an impressive feature that involves the use of artificial light coming down from the ceiling, making the spaces feel taller, as if there is no escape. Another interesting point that is worth mentioning is the fact that, besides the neon signs, we almost never see the actual source of the artificial lights. Depending on the scene, those sources change in position and color in order to emphasize something important, such as the faces of the characters, sometimes from one side, sometimes from the bottom up creating interesting -and sometimes disturbing- shadows. At the same time, it is important to note that there is a distinctive feature in the scenes depicting both the high class society and the working class, lighting-wise. Cold light is used extensively in the office scenes, while a more colorful, golden light is used in the scenes depicting the high society sets, such as the restaurants and the parties that the character attends. It is very rare within the film to see actual sunlight permeating through the windows and into the spaces, and even when it does, the light is pale and dull, almost gray, continuing with the overall atmosphere of the movie. Gilliam is known for his extravagant sets and decorations¹, at the point of being recognized for his unique style of presenting a story consisting of two sides: the ill-fated society that relies on technology and the people that holds on to their fantasies, to their souls and what makes them human in the first place. In this particular film the message is delivered in a very strong manner through the sets and the moods created by the artificially lit interior spaces and the position of the fixtures that deliver it. Arturo Morales ID: 20497963 ________________________________________________________________________________

|

|||||

| 10. |   |

||||

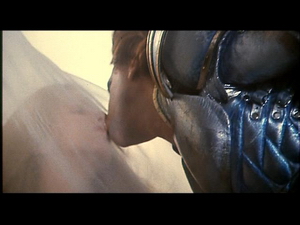

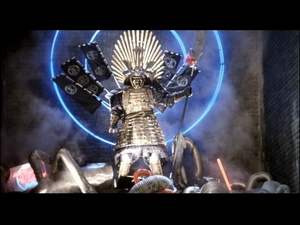

Morgan O'Reilly Terry Gillam’s ‘Brazil,’ utilizes dream sequences to further the audiences’ appreciation of main character, Sam Lowry’s, plight in a convoluted and dystopian world. Through Sam’s dreams the audience is able to experience his fantasies which contrast strikingly with his reality. In the earlier stages of the film these dreams create a majestic world in which Sam is powerful and in control; he is superhuman untethered from even the ground. He soars through the air, clad in winged, angelic armor, swooping through clouds over an untouched utopian landscape towards a beautiful blonde woman. A reoccurring and mystical character in Sam’s dreams, this woman floats in the air amidst layers of gauzy wispy fabric, through which Sam elegantly kisses her, before flying higher into the sky. This dream is abruptly interrupted by the obnoxious buzzing of a telephone. Sam is woken by a call from his employer to find that his apartment lost power at some point during the night and he is late for work. As he quickly prepares for the day Sam’s highly automated apartment fails to perform any of the tasks it has been automated to complete. As the film progresses it is revealed that the dysfunction of Sam’s apartment is but a minor example of a greater bureaucracy in which nothing works logically. Sam, as a government employee is a powerless cog in this destructive machine and as a citizen he is a tragic victim of the system. Sam’s dreams contradict his reality as much as possible revealing his underlying desire to escape this life and further setting him apart from a disturbingly accepting population. As the film progresses and Sam becomes increasingly frustrated with the system, eventually actively breaking the law to find the real woman of his dreams, the purity of Sam’s fantasies are threatened. Skyscrapers explode through the ground of the idyllic landscape that Sam soars over, cutting into the sky and interrupting his path to the woman of his dreams. The open landscape becomes a grid of monstrous skyscrapers, through which Sam searches for the blonde woman. Held captive by, what appears to be a robot Samurai warrior and an army of hunch-backed creatures with disturbing baby face masks, Sam fights desperately to save this woman. His dreams, which once acted as an escape, turn to nightmares which parallel Sam’s waking life. In this way the dream sequences heighten the sense of danger in which Sam puts himself and the terror that he is experiencing. Even his fantasies deteriorate and cannot provide the power and freedom he longs for. As the film continues Sam risks everything for a life with the woman he loves and the line between Sam’s dreams and his reality becomes less and less apparent. Rachel Armstrong describes the effect of this transition in her article ‘Cyborg Architecture and Terry Gillam’s Brazil': The central character, Sam Lowry, is only able to step out of the city through his vivid dreams. During the narrative, he loses his ability to distinguish between his unconscious fantasies and the metropolis, so that, effectively, he becomes a member of the audience. Once Lowry transgresses the expectations of a character in a film world, he brings the threatening world of Brazil out of the screen and into the auditorium. As he repeatedly crosses the borders between the film narrative and our imaginations become blurred, and the threatening consciousness of the dystopian metropolis evolves into a believable threat. Our nightmares become real. This concept is most effectively implemented in the conclusion of the film. As Sam is about to be lobotomized, the audience is tricked briefly into believing that he is saved by a team of rebels, who the government would classify as terrorists. Hope and the idea that the system could be beaten, that good could prevail, that Sam’s fantasy landscape could exist is given to the audience and then jarringly ripped away. This dream sequence is effectively used to convince the audience that to doubt the influence of the ruling power is completely delusional. Armstrong, Rachel. “Cyborg Architecture and Terry Gillam’s Brazil.” In Architecture + Film II, edited by Bob Fear. London, UK: Wiley Academy, 2000, pg 56. Bibliography Emma Dibdin. 10 Controversial Movie Endings: ‘Blade Runner,’ ‘Se7en,’ More. http://www.digitalspy.ca/movies/at-the-movies/a492139/10-controversial-movie-endings-blade-runner-se7en-more.html#~oBWap7c0LlNYBO Maslin, Janet. “The Screen: ‘Brazil,’ From Terry Gillam.” New York Times, December 1985.

|

|||||

| 11. |   |

||||

Patrick Rossiter I believe the intentions of the film in regards to portraying beauty in a dystopian society was probably to fundamentally disturb the viewer but also make it entertaining to the point where the viewer can only laugh in bemusement. Some of the core ideas of “beauty” that Gilliam may have been trying to communicate within the storyline of Brazil: -A shallow society with an appreciation of vanity and over the top fashion. -Cosmetic operations are common place and they appear to not work at all and even malfunction. -Use of prosthetics to create shocking effects –disturbing and at the same time producing comedic aesthetics. Gilliam has created a dystopic and shallow world where characters are addicted to plastic surgery. This cosmetic augmentation is held in high regard within the society and characters seek it at any cost, even if it involves an acid treatment or potentially being fatal. Regarding Brazil, Gilliam was quoted as making commentary on the "craziness of our awkwardly ordered society and the desire to escape it through whatever means possible."1 Superficial and status obsessed characters are more than happy to receive cosmetic treatments which don’t work and make them appear worse. It is astonishingly close to the modern day plastic surgery culture regarding Hollywood personalities. Gilliam represents this concept well with the idea of flawed technology and the visuals that go along with this concept. The use of the special f/x and make up to stretch the skin of the mother of Sam Lowry, Ida, produces a terrifying effect which drives home the idea of a distorted world where dicey medical practices are the norm. The later parts of Ida’s initial cosmetic sequence involve wrapping cellophane around the characters face which by all accounts would suffocate someone. This type of imagery is more associated with violence or aggression in film and it becomes a point of interest as now the viewer is led to assume that this will not lead to suffocation but to some type of beautification. This reverse use of imagery forces the viewer to understand that the world the story is created in is a disturbing and perhaps unethical realm, but still it is a comedic place where we have to laugh at how the characters perceive themselves. The ridiculous visuals not only make Brazil lively, but also push the audience to deliberately think about the obvious irrationality in reality.2 The dehumanization of the characters presents a compromised view of ethical and moral ideals within this created society. Gilliam uses f/x with astounding efficiency as the stripped down technical world makes all these happenings that much more believable and creates an immersive experience for the viewer. As Gilliam depicts the superficial portrayal of beauty he uses the women from Sam’s dream as a form of ultimate beauty in a more typical and predictable way in film. By placing her in an untouchable world inside Sam’s dream in bright and pure scenery the viewer understands that she is the depiction of ideal beauty to Sam. I would compare the use of f/x to that of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Metropolis. The Cabinet of Dr.Caligari – The use of heavy facial makeup to create more dynamic characters allows the viewer to experience the film with more of an emotional connection. The darkened eyes of the antagonist characters communicates that these characters are not to be trusted and devious. Metropolis - The beauty of the android being so powerful that it is able to control men, blinding them with her looks and charm is comparable to the beauty Sam obsesses for in his dreams. 1 “Brazil,” last modified April 4th, 2014, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brazil_(1985_film). 2 “Brazil (Terry Gilliam, 1985),” last modified November 28th, 2012, http://emoryfx.wordpress.com/2012/11/28/brazil-terry-gilliam-1985/.

|

|||||

| 12. |   |

||||

Simone Tchonova The mechanical system’s in Brazil seem to permeate throughout the entire context if the film. In essence they are the dominating architectonic elements of this alternate future reality. These systems are constantly causing huge recurring disruptions within all aspects of the city from personal homes to public circulation paths. Some of these failures include elevators breaking down, and a multitude of short circuiting. The mechanical failures are unquestionably accepted by all of the citizens as a common part of life as we may accept rain showers every once in a while. The citizens do not ever investigate into a solution to create better working mechanical infrastructure but continue to live with these problems to only have temporary solutions. It seems as if the mechanical malfunctions represent the obscure and “malfunctioning” lifestyles of the citizens. They are only fixing their problems temporarily and never looking into permanent more sustainable solutions. It is inevitable that one day the “system” will over load with failures. There are a few characters that understand that the society needs to be changed, and these characters are also the ones who seem uncertain in trusting the sustainability of the mechanical infrastructure. This includes the main character (Lowry) and the freelance mechanical repairman (Mr. Tuttle). The majority of the citizens lack a general sense of responsibility for the world around them as the mechanical systems are blindly connected to have a quick “fix”. An example of this would be when Sam Lowry connects the input and output cable to one another to create a short circuit. There is an overall decline in the society as they keep making new problems by trying to fix the existing with temporary solutions. In The movie Metropolis, there is also a looming presence of mechanical systems over the humans. But in this case the mechanical systems’ pressure over society is not fueled by the people’s own lack of responsibility and maturity, it is fueled by the physical labour of the people who are not aware of the system’s dominating power over them. Later in the film the working men and women discover that the system can be overpowered by humans and that they have the ability to take life into their own hands unlike the society of Brazil who have succumbed to a numbing laziness. |

|||||

| 13. |   |

||||

Yiming Wang

|

|||||

| 14. |   |

||||

Victor Zagabe It is interesting to note that the explosion which occurs in the dinner scene is completely ignored by the cast. It fades into the background as a kind of spectacle in the delusional world found in Brazil where everything abnormal is considered the norm. The explosions in a sense, are only used to provide an atmospheric effect to drive the audience to assume, just as the cast already does, that these occurances are normal. The effect is a numbing one, which forces the audience to perceive these explosions not necessarily as something that arouses fear, but an element which acts to compliment a particular character’s internal frustrations in the same way music tends to build up to produce drama, or suspense. The explosions in this movie create a stark contrast to those found in the science of sleep. The science of sleep portrayed explosions in a very synthetic way, in order to try to encapsulate the illusion of the dream. However, what made the biggest contrast between the movies was that the explosions became the main event the characters were fixated on. It was something very lively in nature that commanded attention and was meant to shock. The xplosions became a stylized caritcature of the effect they were initially intended to reate. Despite the synthetic nature of the xplosions in the science of sleep, it worked tremendously well in the sense that it fit right into the surroundings. |

|||||

updated 25-Apr-2014 9:22 AM