Remember, your images are ABOVE your name.

|

x |

|

|

1. |

|

|

|

|

|

Jennifer Beggs

Describe the relevance of the introductory sequence to appreciating the finer points of appreciating the balance of the film. Do you think this is necessary for this film; for all films? Does it take some challenge away or presume that people will not understand?

In the movie Science of Sleep the opening scene shows a man named Stephane cooking, on what appears to be a cooking television show. He discusses how he is preparing a dream and begins to add ingredients to a pot such as memories, recollections and worries. Throughout the movie the film repeatedly comes back to this scene of Stephane on the television set which balances the narrative of the movie narrative, with Stephane’s conscious (his dreams which stem from his thoughts and emotions).

Without the use of this opening scene I think the audience would have still understood the concept that Stephane was confusing his dreams with reality and that he was having a hard time distinguishing between the two. However the opening scene introduces this theme at the very beginning of the movie which establishes this concept as a significant theme of the movie and the audience does not need to waste time figuring out what to expect the movie to focus on. Right from the very beginning, before the narrative of the movie begins the audience understands the idea of dreams and what they stem from, which we soon figured out is what Stephane is trying to deal with. Though the beginning scene is very “dumbed down” in the explanation of dreams, this technique is able to emphasize that there is something really significant about Stephane’s memories and recollections of the day that manifest themselves into his dreams. It emphasizes Stephane’s paranoia so we are able to recognize it fully while watching the movie. It strips the idea down to give a very straightforward description of dreams. This puts the audience in a mindset to look out for these elements while they watch the rest of the movie.

I feel that if the opening scene was not part of the movie, people would still understand that Stephane is struggling to differentiate between dreams and reality, but it may take longer for the audience to understand what is happening. The beginning eliminates any chance of confusion. The opening scene ensures that the audience knows what to look out for, and they are already thinking of how memories from the previous day will affect dreams and they are instantly already looking out for that in the movie. We, as an audience, are better able to understand Stephane’s point of view and understand how he feels once we’re emerged into the mindset that dreams stem from memories and worries. This also helps introduce the audience to Stephane’s character which important to present at the beginning of the movie.

|

|

|

2.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jaliya Fonseka

Why do you feel that the medium of television is being used as the clarifying means for the connection between dream and reality? Do you think it works? Is it historically appropriate for 2006?

The film Science Sleep as a whole blends its "dream" scenes with its actual stories narrative very frequently throughout the movie. Although there is some form of clarification, often further into the film, there is a bit of confusion and ambiguity as to the depiction of what is dream and what is reality.

The director’s use of the television as the means for the connection between dreams and reality seems to be very fitting as the mediator for both for a number of reasons. One being that it is very similar to what we often do in dreams ourselves. At a certain state of the dream, one sometimes becomes aware of the possibility that they are dreaming and comes into realization that they are in fact dreaming, however, are stuck in the dream until they wake up. Thus, the TV as a mediator works quite well as we often play the role of watching our own dream happen, as we would if it was playing on TV.

The director uses this to clearly illustrate the protagonist’s thoughts, and often his position on certain situations. Once in the "TV show" like setting, we are aware that we have entered Stephan's brain and are viewing his "inner workings." In this space he is accompanied by the people in his life, whose thoughts he infers in order to produce their opinions on his situations - all happening in dream.

In the scene where Stephanie is in this "TV booth," it is made very clear what Stephan's thoughts are as he envisions her loving him and even asking him to ask her to marry him. In such scenes, the thoughts of the protagonist are conveyed and his visions projected on the TV. However, it is not until we see the reality of things that we begin to understand that this is in fact not Stephanie's real feelings towards Stephan, rather, his manifestation of her thoughts.

The effectiveness of the TV as the medium of connection between dream and reality is especially fitting to this film because it is very purposefully orchestrated in a very haphazard way. Thus, instead of smooth transition into a dream sequence, possibly rendered with a filter to further infer a dream state, the director has chosen a very straight forward method that works well with its context.

Films released in the year 2006 included Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, The Da Vinci Code, X-men: The Last Stand and Superman Returns; to list a few. These movies all demonstrate a high level of computerized f/x simulation that is based on the latest film technology. The Science of Sleep, however, again purposefully does the opposite by avoiding these new methods of film production. The director, striving to achieve a certain "feel" creates very crafty methods of composing the film that reject the smooth and slick feeling that other movies often hope to accomplish. Thus, for obvious reasons The Science of Sleep is not historically appropriate for 2006 due to its competitors being so far ahead technologically in fx and execution of such effects. Even so, I find the success of the movie is highly depended upon its ability to be so crafty, and the consistency of this craftiness. It not only allowed to film to be viewed appropriately but also celebrates the stories narrative as well.

|

|

|

3. |

|

|

|

|

|

Miles Gertler

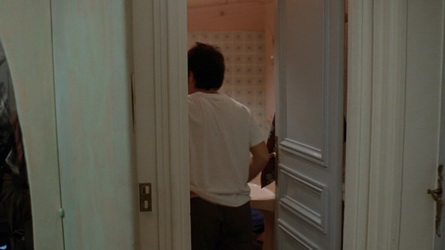

The action of the film consistently uses doors as thresholds for both cutting from scene to scene as well as portals from which to view a scene. Compare these two uses of the doorway in terms of creating an effect or feeling for the scenes.

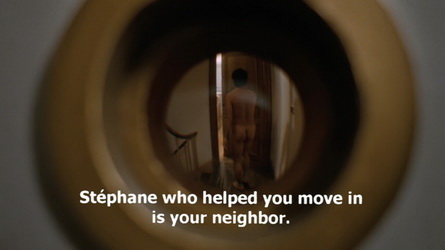

In Michel Gondry's 2006 work The Science of Sleep, Stephane, the enamoured protagonist, confuses his dreams with reality, a phenomenon which generates a diverse array of cinematic effects for the film as a whole. One device that Gondry employs in translating Stephane's syndrome to the film's representative method is the object of the door, both as a threshold to cut from scene to scene, and also as a portal from which other scenes are viewed.

When doors are used as a cutting device, the transition from one scene to the next is abrupt insofar as the movement through time and space occurs instantly. Conversely, peering through the door's portal from one space to another gives a contextual stability while still portraying the transition between scenes. This dual use of doors parallels Stephane's confusion of dream space with that of reality, the perception of which is encouraged by Gondry's abrupt yet seamless transitions from reality to the vivid realm of the unconscious.

Indeed, Stephane often moves from or within an apparently normal environment where a slight peculiarity will continue to grow in magnitude until it is clear that the audience is confronted with the protagonist's dream. In this way the transition from reality to dream is both abrupt, in that it is sudden, and fluid, in that no explicit border gives definition to the transition.

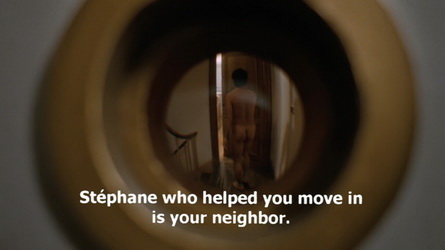

Where Gondry uses the door as a cutting device and where he employs its voyeuristic qualities as a visual portal indicates subtleties about the narrative elements in question in a given scene. For instance, the slamming of the apartment door punctuates a fight between Stephane and Stephanie in the space in between their units, immediately followed by another scene in another location and time. Here the door offers a transition as emphatic and impassioned as the narrative content preceding its use. In an earlier scene, Stephane peers through the peephole to observe Stephanie in the hallway. He then returns to busying himself in his apartment, which subtly evolves into the world of his dream. Here the fluid transition through the peephole is emblematic of the deep connection that his dreams have to reality (the visual, perceptible through a particular lens) and their simultaneous disconnect from it as well (though elements of reality are present in his dream, it has no grounding in it).

The use of the door as a voyeuristic peephole elaborates on a pre-existent trope of French film, where the sheer density of the romantic metropolis, Paris, generates architectural scenes that allow for privileged perspectives between the dwellings of neighbours. In Jean-Pierre Jeunet's Le Fabuleux Destin d'Amelie Poulain, part of the plot relies on the ability of the protagonist, who shares the child-like qualities of Stephane, to peer from her apartment into that of a neighbour she admires. Furthermore, one can imagine that the tightness of the actual set would contribute to the desire to film at point-blank range, as is experienced when looking through the peephole.

|

|

| x |

4. |

|

|

|

x |

|

Suzan Ibrahim

The use of the out of doors - natural landscape - is reserved for the deep dream sequences (ones that happen while he is in bed). Why do you think this has been done? How does this impact the effectivness or reading of these dream sequences? (do not answer David's question below)

The main character has just moved to Paris again. It is unfamiliar to him except for his childhood memories in his older apartment in which he used to live in with his family. This time he is however all on his own and can only find comfort in his own familiar mind. One of his deeper deep dream sequences is him flying over Paris as the city below him looks almost threatening and strange. The reading of it still implies that he is quite distant from that reality in which the city could hold for him and that he has nothing to cling on to for weight. His mind remains his own release to the unfamiliarity surrounding him.

Another recurrent scene is when his dreams take place within a cave. A cave usually signifies an isolation from society and loneliness. It is his distance from the city and unfamiliar or familiar places. This is the type of reality he finds comfort inside of his mind and it becomes a ground to test out his own ideas before applying them in his real life. An example was when he figured out he would transform his neighbour's toy.

These scenes help the viewer to delve further and understand the character of the main figure as well as relate to his condition and fears. They also provide creative and exciting way of understanding the mind of a person and create an experience out of what usually are just thoughts or dreams.

|

|

|

5. |

|

|

|

|

|

David McMurchy

For the most part the scenes shot in the city streets of Paris have their action based in reality. There are occasional daydreaming sequences that are attached to the city scenes but these are rare. Taking care not to answer Suzan's question above, why do you think this has been done? How does it impact the reading of reality in the film?

The dream elements in the film The Science of Sleep are firmly rooted in Stephane’s inner thoughts and fears, and represent his most private sentiments. It is fitting, then, that the majority of the elements of dreaming that he projects take place either in completely artificial claymation environments or in the private and semi-private places that he connects with. It is only when he is in a place where he feels comfortable can he let his mind wander and take over his vision.

The city of Paris, then, is the grounding in reality that is his day-to-day life. It is the reality that he passes through from one dream to the next, and in a way is safe from his insecurities and doubts because what is simply is. When he has waking dreams, his insecurities are elevated, and his sense of safety from being purely in the real world and not trapped analysing it from his ‘brain room’ is removed. The waking dream shows that no matter how ordinary and ‘real’ his environment and actions are, he is governed and affected by his uncontrollable thoughts. His reality is one in which he cannot escape his imagination and insecurities, even in the bastion of security that is Paris.

|

|

|

6. |

|

|

|

|

|

Benny Or

What exactly are we to believe of these scenes? Whose thoughts are they? What are the cinematic clues left by the director that lead you to this conclusion?

The film begins with Stephan as a reality television show host in which he takes a commanding role in the actions of his dreams. However, as the movie progresses, the distinction between his dream world and reality begins to blur as fabrications of his mind surface into the real world. An example of this is when he dreams of writing a letter to Stephanie but in fact actually does so without realizing it. When Stephanie confronts Stephan with the letter later however, Stephan is confounded by how she had perpetrated into his dream world to acquire this information. Through this you can see the struggle that Stephan has with understanding his own reality. These dreams further manifest themselves into reality in sequences such as the cellophane that comes out of the tap and the clouds of cotton that floats while being tossed in mid air. These sequences makes the viewers question if they are actually watching reality unfold or had they been conned into believing that what they were perceiving was yet another figment of Stephan's imagination. This question is further provoked since it appears that Stephanie is also able to see the hallucinatory nature of the action. This leaves us with the possibility that perhaps we were taking part in not Stephan's dream but Stephanie's instead.

Near the end of the film when the couple says their last goodbyes, a cigarette is thrown out of the window and lights a man on hire. The audience knows fully well that this was fictional but at the same time recognized that they were indeed watching reality because of the nature of their conversation. This leaves me with a last interpretation of the film where one questions their own acceptance of reality. It reminds me of the movie Big Fish by Tim Burton where the character is told his birth story by his father. This story was riddled with adventures and make belief characters that created a fantasy world of sorts. Edward, the main character however does not believe this fairy tale story and instead just wanted to hear the true account of his birth. At the end however he realizes that sometimes although fiction does not give a true representation of history, if it made a better story, it was sometimes worth believing. Similarly in "The Science of Sleep," the man on fire made a much more entertaining conclusion that gave the melodramatic sequence a uplifting atmosphere. The viewers no longer are troubled by the need to understand who's dream or reality they are watching but accepts what they see as their preferred reality.

|

|

|

7. |

|

|

|

|

|

William Pentesco

Watch the film for extreme high angle shots. Why are they used? How do they propel or alter the narrative of the film? Who is the viewer or point of view meant to be? Are they different when he is awake or dreaming - both in terms of point of view and reading?

The high angle shots are usually used as transition shots when Stephane is traveling from one place to another in either a dream state or conscious state of mind. There are three areas where these types of shots show up: One is the transition during consciousness, Two is transitions in a fully immersed dream state, Three is the in between state when you can tell if Stephane is awake or asleep.

The fully conscious high angle shots usually take place when Stephane is traveling through the city. Either when he is going to work, or when he is traveling up and down the staircase within his apartment. These shots have narration over them sometimes, which is one way that the movie gets propelled. The other way is that these shots set up context in which the movie takes place. Grounding the work as a whole. The audience is the main viewer of these shots.

The full dream state transitions are completely fantastic. The high angle shots mostly exist when Stephane is flying over the city of his creation, and he is looking down at all the dancing cardboard buildings. The point of view is Stephane himself, as he sees the world around him. This propels the movie in the way that it gives us a glimpse into his world. We see the wonderful and playful inventions of his mind and how he has so much fun going through it trying to find a way to win the heart of Stephanie.

The last instance of high angle shots happen in this state of semi-lucidness. Now I call it this because things happen that make the viewer wonder if Stephane is asleep or awake. One example is when he throws Stephanie’s cigarette over the balcony and the man below bursts into a fire comprised of cellophane. I believe that these shots are to be viewed from a combination of Stephane and Stephanie, their combined childlike imaginations bring these moments to life. This propels the narrative of the story as it shows the connection that these to characters have with each other

|

|

|

8. |

|

|

|

|

|

Emmanuelle Sainté

Watch the film for eye level vs slightly above eye level angle vs slightly below eye level views. Why is each used? How do they propel or alter the narrative of the film considering that the change in level is quite slight?

The extreme subtlety of this effect meant that, although it was used relatively frequently throughout the film, it was rather difficult to watch out for. However certain instances of its use struck me particularly, which helped me form a general impression of their meaning and purpose in this film.

Part of the subtlety of this effect is that it is at times difficult to tell whether this effect was a result of the constraints of the filming conditions, or a part of the overall artistic vision of the film. For example, in several instances, when filming a scene between the two apartments, the narrowness of the landing meant that in order to get a wider shot, the camera presumably had to be positioned on the stairs, resulting in a slightly lower angle.

The first intentional use I could note was in the one of the first dream sequences, where Stéphane finds himself back in the office, and is struggling to accomplish his work with what, when the angle is changed, are revealed to be impossibly large and clumsy hands. A similar low angle close up is used much later in the film, when he visits his coworker’s apartment and is despairing over his feelings for Stéphanie. Both of these scenes were moments of great emotional distress for the main character, moments where he was struggling with feeling lost and powerless against circumstance – in the first instance, being stuck at an unfulfilling job where he was not respected, and the second, dealing with his feelings for a girl which seemed unrequited.

The other instances of shots using angles varying slightly from eye-level that I found notable were moments where Stéphane and Stéphanie shared the screen. These all depicted moments of relational tension between the two characters. For example, a slightly lower angle was used in the shot where they were building a scene of a boat on the water. This is the scene where Stéphane gives his neighbour a gift, and there is a sense of their bonding, and growing closer. Later, a slightly higher angle is used when he goes to her apartment to say goodbye right before his return flight to Mexico. After sharing a moment of friendship and pure understanding, they sit on her balcony and the audience can sense that their relationship has shifted, that they have undergone a rift, and that his clumsy attempts at reconciliation is pushing her further away.

Therefore, these uses of shots that vary slightly from the standard angle are used to subtly indicate changes in the main character and in his relationships with those around him.

|

|

|

9. |

|

|

|

|

|

Tristan van Leur

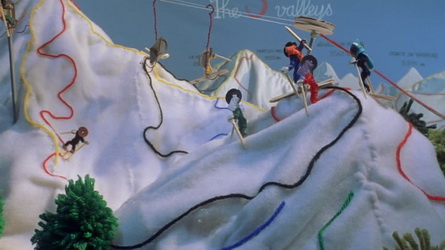

Discuss the set, setting and cinematic construction of this dream sequence. How does it fit into the narrative? What propelled it and where does it lead?

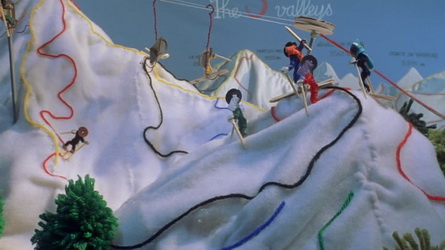

In the above scene, it was constructed using cardboard buildings coated in images of the houses. Each house was set into place and then the scene was shot with a camera on a boom. This cartoonish creation of the city contributed to the bizarre world of his dream sequences, but maintains a surrealistic but realistic feel, enough so to blur the lines between reality and his dreams. The smashed house was then a roughly constructed set at full scale.

These scenes provided a prime example of the narrative of the film. He enters the scene chasing Stephanie, displaying his obsession with her, and the way it affects both his dreams and reality, and the way that in his life, the two are one in the same. The effect of the scene with its cut-out yet realistic feel, is a prime example of Michel Gondry’s ability to create a bizarre parallel dream world that sometimes is laden with the ridiculous, and sometimes close to reality, much in the manner that an actual dream is.

The scene is a prime example of Stephane’s bizarre pursuit of Stephanie, where he searches and discovers new ways to introduce her to his creative and bizarre world, one in which reality is rarely clear, and his imagination and dreams dictate.

|

|

|

10. |

|

|

|

|

|

Benjamin Van Nostrand

Compare the inferred position of the audience in these three dream settings? Compare this to the variety of dream sequences in the Wall. Very different films, but...

In The Science of Sleep, the camera's point of view becomes an active participant in the scene, and by extension the film's viewer becomes a character. The position of the camera implies involvement somehow. Within these three particular clips, the camera point implies:

1) studio audience or cameraman (in addition to set and placement, Stéphane often breaks the Fourth Wall and semi-addresses the viewer directly) Though direct, its lack of subtlety detracts somewhat from the effectiveness of recognizing the camera as another character. We, as the desensitized and hard-to-impress seen-it-all viewer, are nonplussed by short and witty fourth-wall-breaking asides, so this scene doesn't hold nearly the strength its directness would imply.

2) The semicircle formed by the characters around the dream Stéphane's desk is completed by the position of the camera, implying that the viewer is an unseen but openly acknowledged fourth character within the scene. This, I would say, is the second-strongest manifestation of the camera-as-character phenomenon of the film.

3) The position of the camera within the shot and the act of the main character walking away from the beautiful monstrosity of the horse typewriter, as well as the framing of the typewriter within the shot, gives the typewriter compositionally more importance than the retreating figure of Stéphane. If the camera were to track Stéphane, or follow him on a dolly shot, (as would be fairly standard) then the typewriter would become just an interesting set piece, and the camera would preserve a sense of invisibility. Instead, an unspoken dialogue develops between the camera and the typewriter.

4) Most strikingly to me (striking because the effectiveness of the shot remains with me even though I was viewing it in the partially-dazed state of my Tuesday morning semiconsciousness) is an establishing shot near the beginning of the film that shows Stéphane unloading his possessions from the taxi cab. When he is finished, standing with the pile of his worldly possessions on the sidewalk, the taxi cab pulls away with the camera inside it, involving the audience themselves in the act of abandonment and heightening Stéphane's alienation from what might be considered the 'normal' world. Though it might seem odd, this particular scene was for me one of the most poignant of the film.

Conversely, the dream sequences of The Wall are very flat – the camera is an invisible and unacknowledged phantom, and in the few cases where the camera actually moves during the shot it does so in a very deliberate and detached way. For the montage near the film's end, where Pink and his chair/lamp/TV surroundings jump from location to location, the scene changes do not cause changes in camera position. (indeed that seems to be the point) Soldiers run around, over and almost through the camera's point of view, and the camera's position appears in places that would make no logical sense if the intent was to suggest a camera-as-character effect.

|

|

|

11. |

|

|

|

|

|

Shane Neill

Discuss the manipulation of the sound in the film. How is the sound differentiated between the dream and reality sequences (if you find that it is). Are there any auditory clues that assist the viewer in interpreting the nature of the dream sequences, as he does have a number of distinct dream types/settings.

The filming of The Science of Sleep is divided between waking scenes shot en situ in Paris and dream scenes shot in a rural studio. This distinction plays an important role in the soundtrack, and more generally draws attention to the role of sound in daily life. In the waking scenes, the constant din of the city is present in the background. Inside the apartments, the buzz of the street below mixes with the high-pitched sounds of lights and the hum of the HVAC equipment. In the office the high buzz of florescent lights blankets the soundtrack in the aural equivalent to their offensive light. In the dreams however, a very deliberate control of the soundtrack is exercised. The studio setting eliminates the ambient noises of daily life, and the musical score takes precedence. Jean-Michel Bernard’s score exhibits his gentle sensibility for simple melodies and dreamy, innocently-enigmatic harmonies that sound like they could come from a music box unearthed in an exotic, chance-encountered antique shop. Nonetheless, Bernard is able to layer and deploy his compositions to create a wide spectrum of atmospheres. In the opening scene, Stephane gives us the key to understanding his dreams that translated to the composition of the film score:

As you can see, a very delicate combination of complex ingredients is the key. First, we put in some random thoughts. And then we add a little bit of reminiscences of the day, mixed with some memories from the past—that’s for two people. Love, friendships, relationships, with all those ships—together with songs you heard during the day, things you saw, and also personal—...

Generally speaking, Stephane has three types of dreams: reminiscences, anxiety dreams, and fantasies. Each employs a different strategy towards creating a sound track. (These are not exclusive or strict lines. Many dream sequences contain elements or hybrids of multiple dream types.)

Reminiscing dreams typically start out in Studio Stephane TV. The soundtrack alternates between kitschy musical motives on drums and organ that are typical of late-night or local television shows. As Stephane drifts from the introduction of the material into the reminiscing, faint tones are discernible in the background. There is a light oscillation between mid-high notes that creates a calming sense of rocking. In these dreams characters speak in soft voices. Sometimes Stephane goes into a liminal state between waking and remembering, and windy or breathy noises, voices, and sounds from the waking world ebb and flow into the soundscape. Otherwise, Stephane enters a very concentrated state or remembering—as he does when remembering his father. In this scene, there is total silence aside from the echoey, sparse, and solo melodic line.

Stephane’s anxiety dreams typically take place in the exaggerated office set. The soundtrack for these scenes creates a sense of sonic anxiety with juxtaposing instrumentation, rapid textural change, and typical horror movie sound effects. The score is composed of two ensembles, a relatively full studio orchestra and an amplified rock ensemble. The orchestra is underscored with low winds creating a suspenseful sense of dissonance. Strings create accent as they move about angularly in high register clusters. The rock band comes in loudly with no relationship to what the orchestra is doing. Between the two ensembles, a cacophony forms that is further agitated by shrill object sounds like the crawling electric razor creature. Interestingly, in the chase scene that takes place in the city (toward the end of the movie), in order to eliminate all of the ambient city noise, they have to engineer all of the object and action sounds to dub over the sound track. Layers of sound and score are then built up in a similar manner to that above.

The fantasy scenes are perhaps the most simple elements of the soundtrack. Stephane’s fantasies are marked by an aural gentleness. He speaks to Stephanie in a soft mezzo voce. In the cave with Stephanie, her stuffed animals come to life with characteristic and endearing sounds that add a layer of ambience under the composed soundtrack. Stephane narrates, “their delicate, unfinished appearance is friendly... and they are quiet.” This is the perfect description for the accompanying music. The score is a simple, measured, highly-reverberant melodic line played by some measure of synthesized vibraphone, and the absence of musical accent creates a sense of temporal suspension. In the following skiing fantasy skiing on the felt mountain, this melodic line is further orchestrated with the cello in unison with the synth melody and filled out with accompanying strings.

While Jean-Michel Bernard’s soundtrack is perhaps just a very good example of a contemporary compositional idiom, its nuanced deployment is worthy of critical examination. Though no critical work can be found on Bernard, continuing success might draw greater attention to his work in the future.

|

|

|

12. |

|

|

|

|

|

Michelle Greyling

The live action scenes of the film (the apartment scenes) were filmed in a real apartment. Taking into account the discussion of this in the documentary short, how do you think this worked into the juxtaposition of the real/dream sequences that took place in this setting? What were the benefits (or problems) associated with using such a tight set?

The apartment, where most of the live action scenes in "Science of Sleep" were filmed, is the real life childhood apartment of the producer of the film, Michel Gondry. In many instances, the content of Stephane's dreams are filled with the actual documented dreams of Michel Gondry. For example, in the film Stephane dreamed that his hands are monstrous, which is in reality a re-occurring dream of the producer, Michel Gondry. One interpretation of the "real apartment" is that it is represented in the film, by Stephane as the dreamworld of that same space. Several actors and crew members that worked on the set of the film, speculate that Stephane could be the alter ego of Michel Gondry. We all tend to dream often about those spaces, people or objects that are most familiar to us. The presence of the real apartment setting in the film would then be essential to represent Michel Gondry's dreams. The fact that the apartment was "real", support Gondry's use of "real life" dream sequences. The "apartment" become an object of both Gondry and Stephane's childhood memory of place. This space represent safety, comfort and their childhood innocence. The apartment is used by Stephane as a literal escape from life and perhaps similarly by Gondry in a dream sequence.

Another interpretation, suggest that the character of Stephane is an actual representation of Michel Gondry. Yet another interpretation, suggest the film to be merely based on certain real life events that occurred in the life of Michel Gondry. The "real" child-like boys bedroom, become Stephane's literal escape from the outside world, similar to his refuge to the dreamworld. Stephane escape the adult world by retreating to the comfort of his childhood bedroom where he develop and regain child-like characteristics. The real apartment provide Stephan with very concrete images of space and lend to his dreamworld a characteristic that the other settings such as the field, cardboard studio or cave setting did not. The use of a "real apartment" allows much confusion for Stephan when he tries to differentiate dreamworld and reality. For instance, when he find's himself standing in a random field or in the cave setting, he grasps instantly that he is definitely in a dream state. This is not the case when he is in a dream state in his real apartment, where he could easily believe that he is either dreaming or not. Toward the end of the film the real and dream sequences become very blurred. The use of the real apartment in this case, play into emphasizing the confusion between what is reality and what is not.

A more literal interpretation of the presence of the real apartment suggest the exact opposite. Due to the fact that the apartment is literally the only "real" setting in the film, compared to the more dream-like settings of the cave, field and cardboard studio it present to Stephane the only foundation of reality.

The content of the dream sequences is often filled with familiar objects in the real apartment, such as the felt horse and time machine. These familiar articles, similarly support the mental connotations between the reality and the dreamworld. Several of Stephane's dream and real life content, mimic his father's magical abilities, in a child-like manner. For example, the "time machine" and "thought bicycle helmet". Similarly, Stepanie's apartment depicted a very child-like character. Her bed is accessible only by a ladder and every open space in her room is filled with soft toys, dolls, yarn and paintings. She expresses most her creative ideas from the perspective of a child.

In the live action scenes of the apartment setting, I only became aware that Stephane entered a dream state, when the ordinary objects in the space became extraordinary. An example of this is where the water pouring from the tap is represented as cellophane paper or when the cotton wool started to float like clouds. Similarly, the "real" and "dream" sequences start to draw from one another. The dream and real sequences are no longer separate and become deeply intertwined, as the one became the other. This increased to the point where Stephan "acted out" what he was dreaming in the space that he dreamed it. An example, is where Stephane fell asleep in the bath tub and dreamed that he wrote Stephanie a note that he slipped under her door. While dreaming this, Stephane sleepwalked and acted out his dream in reality. In this instance, the "real apartment" represent familiar space that allowed Stephane to completely lose control over what is real and what is not. This is differentiated from the imaginative mind created "cardboard studio" setting, where Stephan was more in control.

Toward the end of the film when Stephane announce his return to Mexico he enters Stephanie's apartment to greet her. Representative of his return to the adult world by leaving the apartment, his actions become less child-like. He makes obscure comments about Stephanie's body which contradict his actions in the previous scenes of the film. The words he use, resemble words used by the other adult male character in the film, named Guy. The journey back to Mexico and the departure from his safe childhood apartment represent his return to the adult outside world.

What were the benefits (or problems) associated with using such a tight set?

There were various problems that arose from using such a tight set. The cinematography of the film in the apartment setting tends to vary a lot. The camera shots were often obtained hand-held to ensure that the correct angles and close-up shots were achieved to capture the personal sense of the character. In such a tight set, the distance of the camera to the subject was constrained and the hand-held shots allowed for a greater variation of shots that would not have been able to be achieved otherwise. The actors were often cut to in a different scene to allow the shots required for the scene. Often times in such films, the real interior scenes would be created with only two or three walls and the fourth wall would be eliminated to allow for the manoeuvring of the camera during the filming process.

Although numerous difficulties were encountered, several benefits were present as well. The use a of real apartment eliminated the need to construct a space from scratch. The majority of the film was filmed in the apartment setting which would have been kind to the budget of the film. Furthermore, the film crew did not have to move sets too often as the scenes that were filmed in the field, cave or country side hotel were minimal.

http://scienceofsleep.livejournal.com/

http://www.critical-film.com/reviews/S/Science_of_Sleep/Science_of_Sleep.html

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1029430/

http://www.dvdverdict.com/reviews/scienceofsleep.php

http://bluegrassfilmsociety.blogspot.com/2006/10/trevor-williams-response-to-science-of.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Science_of_Sleep

http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/the_science_of_sleep/

|

|

|

13. |

|

|

|

|

|

Richard D'Allessandro

Discuss the arts and crafts materiality of the dream sequences depicted above. Beyond making it very obvious that this is a dream sequence, how does the director's choice of material for these scenes feed into the development or support of the narrative?

The narrative of the film, The Science of Sleep, revolves around the platonic love that develops between the two main characters that are united, and eventually conflicted, on the basis of their shared creative enthusiasm. Both accept the waking state of the world with equal acquiescence, reveling instead, in the boundlessness of their private fantasies. These fantasies flourish in dreams, but for them, also take heavy root in the real world through a few intimately crafted objects, with the bones of debris and then fleshed out in their imaginations. The haphazard form of these things, characterized by arts and crafts, is the reason for their first curious attraction in the waking world and a subsequent gateway through which they come to share their fantastic realm. The nature of this imagined would, and the crossover from the waking would to a shared dreamlike world, is the essence of the narrative. The aesthetic and description of this world in the film then, is key to fulfilling an accurate portrayal of the story.

Despite the immense similarity between the personalities of these two characters, they are closed off by discretion and conflicted by matters which, in a dreamlike world, both eventually find inconsequential. Alas, it is impossible for the two to meet for the first time in their dreaming states, and it isn’t until their fantastic idols give each other away, that they begin to explore their shared affinity. Through these things, both characters wish to exist together in a world unencumbered by the physical, political, and social limitations of our regular corporeal existence. Like trying to share a dream, the narrative depicts their struggle to meet each other in an imaginary realm. They begin to build this world, in their waking state, with simple arts and crafts.

Arts and crafts, in and of itself, is a symbol of freed imagination and creative ease. The argument for the art form being, that the creative act of making is in no way stifled by preoccupations and preconceptions of precision and sophistication, which are held as relatively meaningless conceptually. The aesthetic alone carries with it a sense of childlike innocence which speaks to the virgin state of the mind, prior to conformity and mental disenchantment. In this way too, arts and crafts are also a sort of soft but constant icon for the sentiments expressed by the narrative.

As Stephane and Stephanie transition from the waking world into the world of dreams, the director uses a progressing mixture of this materiality to propel the development. As an audience, we are able to make the easy distinction between the characters interacting in a wholly dream state, a waking fantasy, or in the banality and strife of the real world. While these kindred spirits move through reality and begin to operate outside of it, or transcend it, this distinction grounds our understanding.

Quite contrary to what great efforts they actually required of the film’s production team, the sets were intentionally not meant to look meticulously constructed. This attitude supports the fundamental principle behind arts and crafts as mentioned. More importantly though, it establishes the director’s stance on the role of the arts and crafts in this narrative, in that it uses these intimately crafted things as mere props and physical cues for a story constructed and set within the projected imagination of the two main characters. These things, and their arts and crafts materiality, act as a catalyst and bridge between the two characters and their relationship.

The materiality of the dream sequences and their consistency to that of the character’s waking activity, also closes the gap between the waking and sleeping states in the narrative. Used as a narrative device in this way, instead of reading an abrupt contrast and comparison between waking and sleep, the materiality of their dreams and similarity to the fictions they create in reality, allows for a continuation and very serial assimilation of the story. In other words, we are not forced to pause and reflect on the change of setting as a counterpoint, but rather transition from one to another with the understanding that it all pertains to the narrative directly.

|

|

|

14. |

|

|

|

|

|

Talayeh Hamidya

Discuss the use of depth of field as a device in the creation of the film. Include information about image blur and the placement of the characters and objects in the scene. How does this impact the feeling of space in the apartment scenes in particular?

The whole movie as the director mentions directly draws from the spatial and temporal qualities of dream. In a dream there are different incidents happening consecutively without any logical correlation. Image blur is used to create a flow between the scenes, not as many though. Sometimes characters and objects are located in the image in a way unusual to the everyday experience of the spaces or people, very close or odd angles.

In other occasions the depth of field is introduced (very minimal) to emphasis on the relation of objects with people. The horse, the hands and the boat all become elemental objects of the movie as it evolves, all introduced with a blur in the beginning, using the depth of field.

The boat at the end of the movie sitting at a distance from the couple depicts their precarious situation in their shared dream. It becomes to symbolize the mutual desire and the difficulty of fulfilling it. Using the depth of field it is portrayed far when it is close. The depth of field is a powerful device to portray an object/person being out of reach while it is also very close. The hands, also introduced with a depth of field, becoming one when Stephan is playing with his fingers in Stephanie’s room. Later in his dream his hands become out of proportion and he is unable to make things. This is the moment of his heightened frustration in his relationship with Stephanie and again the enlargement of hands and their incapacity to hold and reach for things symbolize, as dreams are, Stephan’s difficulty in reaching Stephanie’s relationship. At the end the horse, which again is introduced to the viewer through use of depth of field, symbolizes solution for the couple, the element they can use to get to the boat (their shared dream).

The tension that the depth of field creates also pertains to the quality of being in a dream, objects are out of proportion and hard to recognize where they exactly are.

|

|

|

15. |

|

|

|

|

|

Maryam Abedini Rad

Although cross dissolve is one of the most common film editing transitions, it (from my multiple viewings of the film...) appears only to have been used this single time. Why? How are the other transitions achieved and why would this not have been suitable as a routine transition. (Please ignore the words on the first image).

The Science of Sleep is a 2006 French film written and directed by Michel Gondry. The film stars Gael García Bernal, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Miou-Miou, and Alain Chabat.

The Science of Sleep, a playful romantic fantasy set inside the topsy-turvy brain of Stephan Miroux (Gael Garcia Bernal) an eccentric young man whose dreams constantly invade his waking life. Stephan pines for next-door neighbor, Stephanie (Charlotte Gainsbourg), but she becomes confused by his childishness and shaky connection to reality. Unable to find the secret to Stephanie's heart while awake, Stephan searches for the answer in his dreams.

Although The Science of Sleep delves into tortured love affairs and the fight for creative spirits to survive in a corporate world, it's loaded with humor and imagination. At least half of the movie warps into the alternate reality that Stephan dreams about, where stunning visuals feature entire cardboard cities, animated disasters happening outside of a window, and boats drifting over seas of cellophane. There are different kinds of eye candy, ranging from high-tech fancy visuals to the simplest kind, like a child's toy moving in stop-motion form. The fantasy sequences provide a perfect contrast to the depressing—and often familiar—reality of what is going on outside of them.

There is a scene that director has used cross dissolve for transition and other scenes have almost simple cuts. It is worth to know what are these transitions and their applications.

Transition Effects

Transitions among shots are considered the punctuation symbols of cinematography; they affect the rhythm of the discourse and the message conveyed by the video. The main transitions used are cut, fade, and cross fade. A cut occurs when the last frame of a shot is immediately replaced by the first frame of the following shot. A fade occurs when one shot gradually replaces another one, either by disappearing (fade out) or by being replaced by the new shot (fade in). A particular case of a fade happens when, instead of two shots, one shot and a black screen are faded in or faded out. Finally, a cross fade (also called dissolve) occurs when two shots are gradually superimposed with one being faded out while the other is being faded in.

Dissolve:

a transitional editing technique between two sequences, shots or scenes, in which the visible image of one shot or scene is gradually replaced, superimposed or blended (by an overlapping fade out or fade in and dissolve) with the image from another shot or scene; often used to suggest the passage of time and to transform one scene to the next; lap dissolve is shorthand for overlap dissolve; also known as a soft transition or cross-dissolve transition.

Cut:

an abrupt or sudden change or jump in camera angle, location, placement, or time, from one shot to another; consists of a transition from one scene to another (a visual cut) or from one soundtrack to another (a sound cut); cutting refers to the selection, splicing and assembly by the film editor of the various shots or sequences for a reel of film, and the process of shortening a scene; also refers to the instructional word 'cut' said at the end of a take by the director to stop the action in front of the camera; cut to refers to the point at which one shot or scene is changed immediately to another; also refers to a complete edited version of a film (e.g., rough cut); also see director's cut; various types of cuts include invisible cut, smooth cut, jump cut (an abrupt cut from one scene or shot to the next), shock cut (the abrupt replacement of one image by another), etc.

The action taking place in the story dictates how the scenes are edited together. The cut and the dissolve are used differently. A camera cut changes the perspective from which a scene is portrayed. It is as if the viewer suddenly and instantly moved to a different place, and could see the scene from another angle.

Cut is sharp so the scene change is sharp. It is direct; it takes you straight to the next scene, most often used in mainstream Hollywood films.

Cross-dissolve is similar to a cut but much softer and takes a while. Instead of having a hard cur between 2 unrelated scenes we can have a cross dissolve that make the transition smoother and softer.

Almost all of the transitions in this film are simple cut. But the mentioned scene has cross-dissolve transition because it seems that those two scenes are not related to each other and when it takes a while the viewer is ready for the change of the scene from an exterior scene of floating the television in the river to the interior scene that Stephanie is sat on the stairs and waiting for Stephan to come back home. The other scenes are more and less related. So, there is no need for cross-dissolve. For instance when the door of the building closes and the door of the unit opens. The director has used simple cut for the transition.

And maybe there is another reason for that, when the TV is floating (Stephan`s friend says…let`s take our mind off the TV because it doesn’t say the truth and doesn’t reflect the reality) we watch the next scene which Stephanie is waiting for him this cross-dissolve as a transition may have this meaning that there is no more transition between reality and fantasy of his mind anymore. This kind of transition can be a symbol of his transition to the real world from the dream world.

http://www.filmsite.org/filmterms7.html

http://www.amazon.com/Science-Sleep-Gael-Garc%C3%ADa-Bernal/dp/B000M4RG7E

|

|

| |

16. |

|

|

|

|

|

Jamie Usas

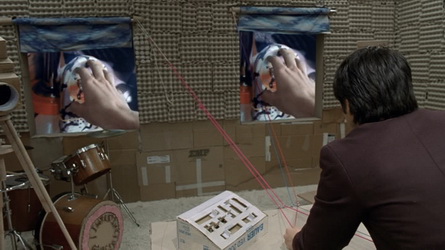

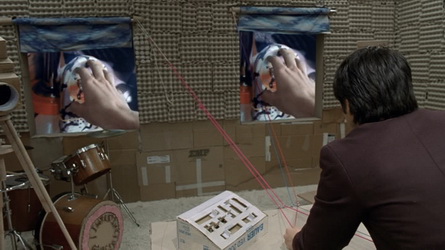

Discuss the effectiveness of the use of back projection for the dream sequences shot in the office. Is any one more successful than the others? If so, why? (I have not included all instances in the image above).

Michel Gondry’s hallucinatory The Science of Sleep rediscovers the (all but extinct) art of rear projection, bringing an honest and handmade aesthetic quality to the film. While traditional use of rear projection has been reserved for the creating the illusion of realistic 3D space in a background plane of the image, Michel Gondry employs the technique to create a surrealist, logical division, separating the conscious and unconscious sequences of the film. Although crude, Gondry’s use of rear projection succeeds more in the realm of performance than in the realm of special effects. The nature of the in-camera effect (rear projection) over post-production effect (chroma key) allows for a level of organic improvisation among the actors involved in the scene, resulting in an arguably more convincing performance. Rear projection provides actual data for actors to respond to, for example; Kerry Grant’s reaction to the plunging crop duster in Hitchcock’s, North by North West. Blue screen/chroma-key, alternately, relies entirely on the mental construction of the actors themselves, to create the illusion of continuity between the real and the virtual as illustrated in contemporary films like Sin City and 300. Most clearly visible during the “God scene”, Stéphane Miroux, actor Gael Garcia Bernal, dreams of his ability to physically manifest the physical structures of his personal world, while his co-workers gazes in a ecstasy of reverie. By employing the technique of rear projection, rather than chroma-key, both Bernal and the supporting cast of the scene are able to simultaneously respond to the literal image of buildings materializing in space, as oppose to the forced imagining of a virtual space yet to be defined.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|