| |

The

pairs of students below are assigned a pair of images from the film, plus

a keyword or set of keywords. Don't consider yourself limited to referring

to the images assigned (I only have so much space) as there are many more

from the film that could be added to your clue set. Make sure you look

at the images BELOW your names.

You are NOT

to confer ahead of time. Prepare your discussion (keep it to less than

400 words please) based on the frame of reference, I have been there

or I have not been there. You will both be giving answers in

class and we will be comparing the nature of the answer to see how it

relates to the impressions of the film based upon personal experience

of a place, or lack thereof.

Special

question for the Italian students. |

|

| |

1.

Chang,

Clementine

+ Armstrong, Anne-Marie -- foreshadowing |

|

| |

Clementine

Chang:

The Belly

of an Architect is visually stimulating and memorable, which works extremely

well where the technique of foreshadowing is employed. Early scenes are

composed to leave vivid marks in the viewer’s memory by using strong

symmetry, recurring geometry and the general impressive ways of Rome.

For example,

the opening scenes cleverly foreshadowed Stourley Kracklite’s inevitably

destiny. On the train into Rome, the scenery of the hillside cemetery

sprinkled with the many crucifixes created a feeling of unease. From that

point onwards, the viewer anticipates conflict and chaos to erupt. The

film comes full circle at the end when Stourley falls out the window to

end his life. He does so in a Christ-like position echoing the crucifixes

from the start of the film.

Throughout

the entire film, the recurrence of round forms is evident. They allude

to the spherical constructions designed by Etienne-Louis Boullée

and form strong impressions on the viewer early in the film. The beginning

scene of Stourley lying down with his dome-shaped belly clearly displayed

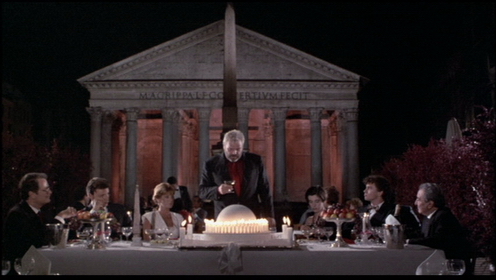

after making love to his wife introduces a chain of round forms to come.

The dome-shaped cake at the first dinner in front of the Pantheon is one

example. In fact, the Pantheon itself also served to remind the viewer

of round forms, even without actually revealing its famous dome. The image

of the crumbled dome cake foreshadowed the deterioration of Stourley,

soon to be manifested by his stomach pains. Further, Louisa’s pregnant

belly also contributes to the list of recurring round forms. The parallel

timing of Stourley’s death cycle and his child’s birth cycle

worked to foreshadow each other simultaneously, as the plot yearns for

an instinctual balance of events.

Anne-Marie Armstrong:

Richly symbolic

imagery provides The Belly of An Architect with several opportunities

to employ foreshadowing, which is accomplished through the employment

of shifts in scale from the strong geometry or symbols presented towards

the films focus, Kracklite.

The film

opens with images pertaining to death, in the form of several crucifixes,

set against the landscape, followed by the scale shift to that of two

gravesites, displaying photographs of the deceased. These images immediately

speak to the viewer of the potential for tragedy to unfold. Retaining

the memory of these two images, we are next introduced to Kracklite in

the throes of a sexual encounter with his wife on his way into Italy by

train, traveling through the landscape towards the city. As an audience,

we are presented with the round spherical ‘dome’ that is his

stomach. Retaining the memory of the two initial images and connecting

them to the introduction of the protagonist, the film foreshadows Kracklite’s

ultimate and painful struggle and his eventual demise due to a cancer

of the stomach.

The aforementioned

image of Kracklite’s prominent paunch becomes the focus of the film

as it unfolds. The image of the Pantheon, of which a dome-shaped cake

is set against, connects again, abstractly, back to the form of Kracklite.

Thus, when the cake is ultimately abandoned in a state of ruin, we are

able to make connections back to Kracklite and his destiny. This is reinforced

later in the film, because shortly after this scene, Kracklite begins

to deteriorate, he begins to suffer from excruciating stomach pains, vomiting

everytime he eats.

|

|

| |

2. Cichy,

Mark

+ Bedard, Joshua -- symmetry of "place"

|

|

| |

Mark Cichy:

The

symmetry of the Pantheon is striking, the execution, given its massive

scale – breathtaking. My memory of this well known relic was made

all the more intimate by the enormous amount of time I spent sketching

and photographing every crevice of her beauty. My intention was to create

a digital version that would compliment its precision. I was humbled by

the complexity of what appeared to be an incredibly simple parti. Incredibly

ornate, yet restrained, the parti was so simple, a sphere inside a box

– a figure of accuracy. Eventually I became asphyxiated in its complexity

and abandoned the project in the best interest of my sanity.

The

sheer scale was astonishing, the tactility of the stone smooth and silky.

The pediment stood proud amongst the piazza, it seemed to float amongst

the clouds, engrained in the stone, a tribute to Marcus Agrippa. The forest

of columns amid the entrance were incomprehensible, pictures do not even

begin to describe the sheer mass they possessed. Clasping my arms against

them barely even accounted for one-eighth their circumference. The stone

was cool, yet comforting; the veins were worn and smooth. I spent hours

studying the structure supporting the pediment, massive wooden beams,

thousands of years old, yet still as strong as the day they were placed.

The doors

were astonishing, also enormous in scale, they required the strength of

at least three or four men to open or close. The iron that protruded was

worn from centuries of use. The hinges were about the length of my leg!

The wood itself was magnificently intact and un-weathered. The entrance

made you feel like you were entering a sanctuary built for the gods.

The first

spectacle that demands your attention upon entering is the intense glow

of the sun streaming in through the oculus above. Its beauty is both breathtaking

and mesmerizing; I stood there for hours, starring as the world continued

to move around me. The coffered ceiling had such depth and created such

striking shadow lines; if I were to reach out my hand I could have felt

the touch of the cold shadowy stone above. The sheer precision and placement

of the drainage wholes in the floor were astonishing, maybe more so, the

fact that they were even conceived of at all. Standing in the centre was

like standing at the centre of the universe; and reaching into the centre

when rain was coming through the oculus was an especially serendipitous

event. It was amazing to see the rain concentrated and controlled at such

a large diameter. Amongst the midst of the restoration were still pieces

that showed their original state. At the base of the dome was a fabulous

colonnade, although rhythmic in progression, this apparently had been

altered over time. Beneath the colonnade, were large vertical columns;

between the columns, the tomb of the Rafael and several other kings. Finally

the alter, stood directly opposite the entrance; in front were about fifty

carefully placed chairs, fenced off with red velvet ropes and remarkably

shiny brass poles. Lit almost entirely by ambient light, the interior

of the Pantheon was an incredibly serene sanctuary. Every surface hard,

yet rich with colour; cool to the touch, and incredibly smooth and inviting.

The exaggeration of scale made me feel like I was truly a mouse amongst

my surroundings.

December

21, 2002 was the last day I sat inside the Pantheon, and I sat there watching,

studying, for almost five hours straight, I took three hundred and ninety-four

photos, and filled three quarters of a sketchbook with notes and drawings

– I will never forget that day for as long as I live.

photos by Mark Cichy

Joshua

Bedard:

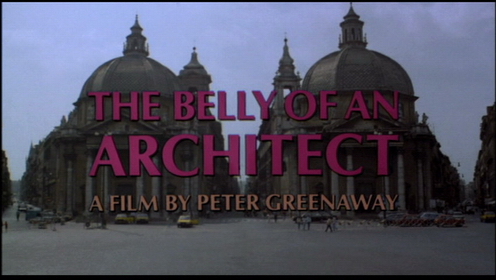

Upon viewing Peter Greenaway’s The Belly of

an Architect, one can quickly see the use of symmetry in numerous scenes

throughout the film. Before I comment and speculate on the use of symmetry

in the film I would like to point out that I have never been to Rome.

Therefore my view is strictly bias through the eyes of Peter Greenaway.

In Greenaway’s film the viewer is constantly confronted with numerous

symmetrical frames. This starts within the film immediately. Right at

the beginning we see a shot that focuses in on a street symmetrically

framed by two classical Roman buildings. Then in the centre we see the

title of the film appear. This is how most of the symmetrical shots within

the film are constructed. They usually consist of a framed view with a

left side that very closely mirrors the right side. These masses help

create a focal point that ultimately provide a sense of place within the

film. In most of these symmetrical shots Greenaway heavily relies upon

the symmetrical order of classical architecture and monuments to establish

the focal point. This focal point becomes a very powerful spot in which

we commonly observe the main character, Stourley Kracklite, an egotistical

architect.

Just as

Greenaway takes us into the life of his main character he also intrigues

us into the city of Rome. Through the use of symmetry he begins to create

a parallel of power between the main character and the city. We begin

to see the quest for power and order throughout the film. We start to

believe that Rome is all about its historical and pristine classical architecture.

We start to believe that these buildings make Rome what it is. We begin

to see the power these buildings posses. However, as the main character

begins fall sick we also start to see more modern buildings. Unlike the

classical buildings these modern buildings (some of which I know very

little of) leave me with no connection to the city of Rome. Unlike the

classical buildings, these non-symmetrical buildings do not posses the

same sense of power. In this sense the lack of symmetry helps depicts

Kracklite’s decline in power.

In conclusion,

Greenaway uses symmetry to place myself within the Rome that I am familiar

with. This is the Rome we most commonly identify through architectural

history books. Again and again these books show the power, order and focal

points created by classical architecture. However, I feel ignorant and

less connected to present day Rome. For this reason when the symmetrical

frames and buildings begin to dwindle and we see more modern artefacts,

I begin to feel more distant and ignorant of present day Rome.

|

|

| x |

3. Gibson,

Nancy

+ Bolen, Matthew -- foreshadowing

coupled with "bookending" |

x |

| |

Nancy

Gibson: Foreshadowing coupled with Book-ending

The movie

begins with the Pantheon looming in the background of a dinner during

which, the project of Stourley Kracklite, an unknown, contemporary architect,

is introduced.. The image of the pound note, lost in the dome cake and

burned by the candles, foreshadows financial ruin and the disease of the

architects stomach. This setting is repeated at the impending death of

Kracklite and the loss of his project to the Italian rival. In the alternate

scene, Kracklites stomach cancer has been established and he is no longer

in control of the exhibition. The pantheon looms in the background as

permanent as ever suggesting the insignificance of modern man against

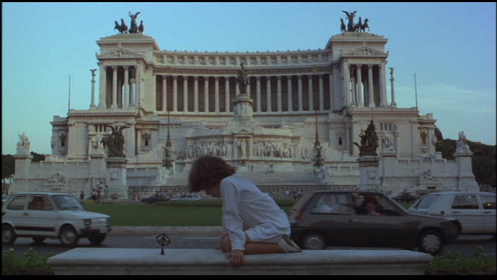

the massive legacy of the past. The massive architecture of the Vittorio

Emmanuel monument punctuates the film, dividing it into episodes. It divides

his experience in Rome into small bites of his life as it deteriorates

around him. He feels he’s being poisoned. He suspects he’s

dying but the doctors are dismissive. He begins to write postcards to

a dead architect. The project is removed from his control and finally

he kills himself. The Vittorio Emmanuel monument remains eternal (at least

until the film rots).

Matt Bolen:

The two images

provided are clear examples of how both foreshadowing and book ending

are used in this film.

The British pound with the image of Sir Isaac Newton being burned symbolically

foreshadowed the destruction of Kracklite’s connection to Boullee

and the exhibition which he had devoted his life to. This was a symbolic

foreshadowing because Kracklite’s connection and admiration for

Boulee was similar to a connection Boulee had for Newton during his lifetime.

The last scene of this film is the view of the classic Roman building,

which was used for the exhibition, with the boy spinning the toy that

Kracklite had given him. This image can be viewed as a moment of book

ending in a very literal sense. This scene was foreshadowed earlier in

the film when Kracklite and the boy met outside Kracklite’s apartment.

From the viewpoint of someone who has never been to Rome, this last scene/

shot could be viewed as a commentary on the architectural permanences

that exist throughout Rome and how they can exist and thrive throughout

many lifetimes. One could argue that this scene could be seen not only

as the ending of Kracklite’s story with his death but also the beginning

of the story of the boy. The story of the boy could be imagined as following

a very different path, however, the identical Roman architectural backdrop

could be used just as effectively thus emphasizing its permanent and versatile

quality.

|

|

| |

4. Olivia

Keung

+ Brown, Liam -- symmetry combined

with use of colour |

|

| |

Olivia

Keung

The role

of symmetry in the film serves a purpose that is directly linked to that

of the colour white: both elements present Kracklite’s early vision

of Rome, a place of stability and eternal, unchanging history. It is the

textbook version of a city where architecture can measure man’s

exact position in the universe. Kracklite begins the film certain of his

own position: he enters Italy as a celebrated architect with a beautiful

wife; his confidence gives him the ability to believe in the geometric

perfection of Étienne-Louis Boulée’s architecture,

although most of it was never even realized. Kracklite is able to work

on his exhibition for ten years without questioning its relevance in the

modern world.

Having been

in Rome will perhaps give the viewer the advantage of understanding the

flaws of this vision more blatantly. Through the experience, one realizes

that when such an idealized vision, such as the Pantheon, becomes realized

as architecture, its existence exposes it to the imperfections and chaos

of reality. In truth, the Pantheon is riddled with bullet holes and other

signs of decay; even the vision it carries has been marred by its conversion

into a Christian temple. It is also surrounded by cafés and banks,

signs of change and newer visions such as the arches of McDonald’s

that faces the monument audaciously: all of these things have been edited

out by Kracklite’s stubborn vision. Similarly, the balanced view

of the clean, white monument of Vittorio Emanuele is, in reality, something

that can only be attained from across the chaos of traffic and tourism

in Piazza Venezia.

It is appropriate

that Kracklite’s idealism begins to deteriorate at Hadrian’s

villa, a place where the emperor celebrates the world for its variety

instead. The injection of colour also shows the invasion of elements that

threaten Kracklite’s solid beliefs. Kracklite in his bright red

pyjamas reveals himself as a foreign agent, ridiculed by his Italian peers

who do not hold Boullée in the same regard. Flavia’s red

couch is the place where Kracklite cheats on his wife, amidst the black

and white photographs on the wall that are posed and frozen. Kracklite’s

eventual downfall is metaphorically reflected in the chaos that he eventually

comes to see in Rome, a city that Boullée never travelled to or

learned to understand.

Liam Brown

Throughout

the film the majority of framed views or vignettes that pose symmetry

are of a positive and negative arrangement: specifically black and white.

Where white may represent the purity of Rome, in its calculated form and

structure, the black is often in the shadows, helping to create a bold

contrast or silhouette often between Kracklite and his setting. Accented

red later builds these framed shots and add to their significance. In

the

case of Kracklite, he exists in the shadow of Étienne-Louis Boulée,

his own character and identity are masked in the figure of Boulée.

He superimposes himself somewhere where he does not belong. Physically,

this is true for the buildings of Rome, but figuratively

this is true when he adorns his abdomen with the body shapes of Augustus.

As Kracklite falls apart so too does our image of Rome as an unvisited

place. Caspazian’s sister throughout the film has been observing

him through pictures and as his life falls apart he is confronted with

her created timeline, a collage of his time in Rome, that is displayed

in a horizontal arrangement, guided by a curving red ribbon. He sees shots

of symmetry arranged in a jagged non-symmetrical order, illustrating the

chaos of

the seemingly symmetrical Rome. Following this he continues into a new

irregularity.

He breaks his remaining sanctity of his marriage on a deep red couch,

with Caspazian’s sister. After this encounter, Caspazian remarks

that “Boulée knew more about colour than Leonardo Da Vinci”,

a statement that Kracklite was not aware of (and Kracklite does not hear

the remark). In the following frame Kracklite is poised on his bed, overlooking

the threshold between himself and many images of the muscular chest of

Augustus. Beyond the pictures is a mirror, where the image of himself

is reflected back at him completing a new kind of symmetry. He is set

against Rome, seeing himself as an alien, but still engaged with his icon.

Colour plays an important role here, as his clothes are rich and lush

with red. He is troubled about his health and his image as well as money

for the exhibition. He scorns his wife for exposing her pregnant body,

but he himself has been photographed without his shirt, bloated with a

different kind of growth. He has been changed by Rome, but Rome has not

been changed by him, as the film ends it recants aprevious setting when

he was standing symmetrically in the Pantheon about to give an address

of his intentions, instead he falls backwards through the very same opening

he posed in front of before, killing himself. Throughout his madness,

there is a departure from the symmetry of Rome, but in the end it shows

that although he had changed, Rome had not, its symmetry continued where

his finished.

|

|

| |

5. Julia

Farkas

+ Chau, Tammy -- bellies... |

|

| |

Julia

Farkas:

Greenaway

uses the image of the belly numerous times throughout the movie to explore

the source and sustenance of our humanity. The movie repeatedly narrates

back and forth between the corporeal bellies of Kracklite, his wife and

his idol - Etienne Boullee, and those of urban morphology- the void of

the piazza, the dome of the Pantheon, the tomb of Augustus….. They

all resemble the expanding space of our insides as they swell with the

sound of a huge mass or dwindle to the silence of a single inhabitant.

The film, however, always keeps us outside of these architectonic spaces,

marveling at their beauty from without, just as Kracklite obsesses over

the untouchable intestines of Boullee. The connotation of the belly here

conceivably deals with the theme of lineage. His obsession with Boullee’s

belly is perhaps a vain attempt to seek the patronage of his beloved mentor,

in effect to begin to understand the character behind the image.

Furthermore,

the belly acts as the source of life and death in the film. Likewise,

the bellies of Rome are the scenes of life and death in the city; the

piazza, the church, the spaces of congregation are the sites of urban

existence.

The space

of the film follows Kracklites’ child from conception to birth while

watching him suffer death, perhaps a necessary course of events in order

to bring life to his creation. The theme of sustenance returns here once

again. The belly an organ that is suppose to be the source of his nourishment

however, is what in the end consumes him.

|

|

| |

6. Adriana

De Angelis

+ Czypyha, Shane -- framing

as manipulation |

|

| |

Adriana

De Angelis --

Framing as manipulation

Peter Geenway

came to Rome in a difficult moment of his life, while undergoing a severe

nervous break-down; his film, The belly of an Architct, was directed right

after. It is notorious that the vision of anything when suffering, expecially

when cancer, depression or obsession occur, is completely different from

the one any person would have in moments of perfect health. When ill,

sickness becomes the frame of anybody’s life that results manipulated

and focused only on peculiar topics, in a distort, haunting and maniac

way. Illeness it’s definitely like watchig the whole world through

a telescope and that’s exactly the way Greenway wants us to look

at his film and at the city of Rome, forcing us to concentrate our interest

only on his vision of things. The empty, iconographic, magnificent, actually

nonexistent Rome that interests him is the one of the two moments of its

splendour and decadence where the leading character is completely alone

with himself: the Imperial/pagan and the Baroque/catholic. Two focal moments

that reflect the splendour and decadence of an architect, Kraklite, and

of a film director, Peter Greenway. Everything and everybody, even Hadrian

and August, Boullée and Newton, around the protagonist architect

(isn’t a film director sort of an architect too?) reflects his feelings,

his fears, his thoughts, his life. The film is a continous demonstration

of how Greenway skilfully handles Rome, its inhabitants, actors and public

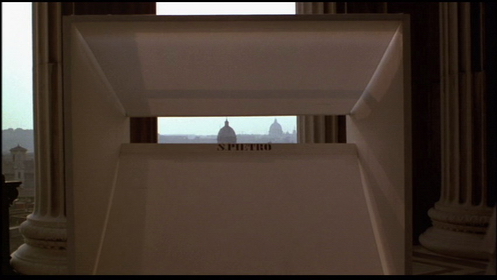

through his story. Emblematic of what we are trying to say are two particular

takes: the first at the beginning and the second at the end of the film.

In fact, the modern pic-nic held by all the charcters in one of the few

remaining buildings of Villa Adriana, because of the particular frame,

it’s magically transformed by Greenway into one of this almost indecent

banquets of the Imperial Rome where everything is sick, particularly people

that participate. At the same way, probably knowing the idea that was

already of Le Corbusier, using an artificial fabric camera set between

two columns of the huge Vittoriano’s balcony, excluding all the

buildings and domes of the breathtaking view, Greenway artfully directs

our regards on the only two he is interested in: Saint Peter and Sant’Agnese

in Agone. Is this his way to indicate a desire of rebirth to a new, more

spiritual, healthier and just way of life?

What is your

impresson of the conflict in the film as it relates to the representation

of the Italians and their relationship with the Americans?

Stereotype

it’s just another form of illness, exactly like cancer, depression

and obsession. It’s a frame that manipulates people’s thiking.

While as an illness I consider it indispensable for the story Greenway

is telling us, it’s to me absolutely incomprehensible in any day

life from which should be banned. I think the world is sufficiently adult

and with no barriers anymore to start looking at people as individuals

and not as representatives of different nations, admitting that we’re

all the same, with the same fears, the same thoughts, the same dreams,

the same faults, the same souls.

Shane

Czypyha:

The city

of Rome, as presented in Peter Greenaway’s “Belly of an Architect,”

is framed as a place dominated by singular elements and focuses set into

a consistent homogenous fabric. Greenaway manipulates shots so that the

cinematography reveals only a fraction of the place and the stories that

accompany. The focus is left on the main character, Sturley Kracklite’s

story.

The hazy view through the small slit reveals an undefined mass. The domed

cathedral, the only building in this view with any definition, rises above

the mass taking the entire focus of the shot. At Hadrian’s villa

much of the shots employed focus only on where the picnic is and hardly

at all on the architecture of the entire space. At the Pantheon the shots

are almost all directed at the fountain, or at the dinner tables in front

of the building. In most of the shots at the place of the exhibition the

view is dominated by the grand exterior staircase. All of these are examples

of how the overall city is neglected in favour of a more focused narrative.

Flat scenes, like photographs or paintings, articulate setting and scenario,

while the articulation of the humanistic side of the film is left to dialogue

as well as placement and positioning of people in the flat scenes.

The shots of the city, which allow focused and fragmented glimpses of

the entire setting, closely parallel Kracklite’s focus on his time

and purpose in Rome. He only sees things selectively, in a way completely

ignoring things integral to his success and happiness. He only sees Boullee,

a theoretical and largely unproven architect, in Rome, the richest architectural

setting in the world. He thinks his wife is poisoning him rather than

the cause of his illness being due to other factors. He sees Caspasian

stealing his exhibition and neglects the fact that he is stealing his

wife.

The framed views are meant to provide a window for Kracklite’s dillusion

that leads to his demise.

|

|

| |

7. Francesco

Mancini

+ Drago, Natalie -- architectural

enclosure combined with "framing" and continuity |

|

| |

Francesco

Mancini

Rome:

Seven Postcards and a bill

Pantheon,

late night

Dear Etienne Louis, I am so happy. Here at last, in the eternal city to

celebrate you, before Pantheon’s immensity, tasting life at its

roots, I do not see nothing but you standing in front of me, as an immense

obelisc. I am not tired of eating so much, not tired of pursuing the effort

of an entire life. I know that this spherical enclosure of perfection,

symbol of perfect and insuperable science, is protecting me.

St. Cracklite, Architect

Vittoriano,

afternoon

Dear Etienne Louis, life seems different today. Last night I saw the perfect

symbol for the exhibition opening: your Newton memorial, strangely but

beautyfully broken in two pieces. Today, except for my wife’s dress

everything was pefect: simmetry, axiality, colour, light, even people.

Looking at them I cannot see nothing but the perfect balance of spirit

and reason pervading your achitecture, pervading me.

St. Cracklite, Architect

Mausoleo

di Augusto, morning

Etienne, today I am furious. This beautiful monument is closed, framed

by gates and chains; i cannot stand this excess of enclosure, of preservation:

this is breaking the continuity of my research. Instead of visiting this

marvellous tomb I will go to the museum..... I did not sleep good these

days. May be the pears, those awful green pears....

Villa

Adriana, late evening

Dear Etienne, I tried to find back my spirit today, having dinner with

my wife, but I couldn’t. I threw out many times these days. It was

painful, as if I was pregnant. I felt spied in the bathroom, are you watching

me? Today I felt safe here, but then in the corridor I had another crisis.

Carcinoma, poisnoning..... what’s happening to me Louis? In the

teatro marittimo I felt somebody’s presence outside, taking slides

of life away from me, still by still leaving me alone. Talk to me Louis....

Stuart

San Pietro,

late afternoon

Luis, today I looked at the doome, it is no longer in the center; out

of focus from the obelisc, the great city belly is still dominating the

void of the Piazza, lightened by a marvellous sunset, but remembering

me the drama of Borromini’s doom and piazza Navona. Axes and shapes

are moving before my eyes, but why do I see only rough greeny copies of

the original? My ambitions and passions are still alive, but what about

my future? It looks like an agony.

My wife is pregnant, did i tell you that? I need more space for the exibithion.

Stuart

Fori

imperiali, evening

My wife betrayed me. I am lost, life has no longer any color, taste or

value to my eyes. I look for you, and I see Piranesi’s ruins thrown

out of Rome’s stomach. Everything I thought to be safely enclosed

in the world’ s perfect frame is now broken into my life fragments.

I alwas climb stairs, but to go where? This cancer is devouring me.

Palazzo

del Lavoro, noon

I would like you to be here today looking outside her window: What a fake

building out there! They claimed they were inspired by your values, Etienne,

but look at those arces: they frame nothing; a concrete structure uphold

them. Now I am in her room looking inside: all this pictures about me,

Kaspar and Julia ... How could I be that blind? Life is obsessed by our

way of framing reality. Despite our passions we try to section it in a

scientific way, to find its true one meaning, but life is not about that.

Passion cannot be enclosed by perfection, it changes: through her eyes

I see a different world. Louis, did you ever speak about love?

The Bill

Dear Etienne your effimeral exibition is starting, my life is ending.

The spherical journey of my life is almost completed now, except for a

last excess: one step back, to my untouchable memories of perfection,

closing my eyes to finally catch the life I pursued and that never was.

See you soon

Stourley

Kracklite

Architect

Natalie

Drago: Architectural enclosure combined with framing and continuity.

In both scenes

the architecture is the physical element that encloses, while Stourely

becomes the enclosed object and the framed subject. His mental state in

each case is altered or affected by being enclosed although the qualities

of the two enclosures are in comparison and contrast with eachother. Enclosed

space alludes to framing by nature of its own physical framework.

By means

of his body language we are able to determine the weight of the enclosures

he subjected to. In the arched hallway the atmosphere is dark heavy and

overbearing and speckled with small traces of light. There he bends and

is ill. It is as though he is responding in a guttural fashion to the

negative aura and feel of the space as well as portraying the illness

that inflicts him. Singling this shot out we may even analyze that his

actions demonstrate his physical and mental condition, the mental condition

affects by the space he occupies in which he is oppressed and enclosed.

In the lighter,

airier corridor enclosure, flanked by tall sturdy concrete columns, Stourely

again remains subject to his condition in terms of his physical setting

and physical ailments. More light penetrates this semi-enclosed space

and overall it feels lighter and less imposing. This space is less oppressive

than the previously mentioned. Although he is still sick we see that here

he stands erect and can deduce that his physical environment has greater

influence, power and meaning beyond that of just setting in this plot.

Still his eyes are downcast as previously, reiterating his condition and

mental state and the fall out of the plot and his character.

These scenes are related and connected by means of the camera work. The

camera provides the opportunity to frame any event. It decided what is

included and excluded within a capture, what is of interest, valuable

or of importance, enabling the directors to convey the message tone and

mood in a scene. The frame of the camera then dictates boundaries, outlines

context and emphasizes forms and gestures.

Scenes are

constructed by fitting and uniting smaller parts of a larger structure

similar to the bones of the human skeleton. In each shot Stourely’s

posture resulting form reflects and defines the structural principals

of the corridors, whether arched or erect in nature. Form always eluding

the physical properties either found in nature or the human body. The

exposed structure, the skeleton, the body, death and decay.

Hence the

framework is based on the principal of a frame within a frame. Delivering

a sense of perspective, an outlook, an understanding, an analogy, a response

and sense of enclosure. All these responses to setting are inherent to

the human psyche’s abilities, visual, sensorial and temporal analysis

of distances, proportions, materiality, weight and lightness and darkness.

Each photo of each enclosure is transitive, characterized by having or

containing a direct object. It is also transitive because the object is

“being or relating to a relation with property that if the relation

holds between first and second and between second and third, it holds

between the first and third elements”, the unfolding and mathematical

relation and rationale of events. Architecturally there is a progression

that is related to or characterized by transition or movement through

and about the spaces. While enhanced and reinforced by setting.

The progression

through the space is accompanied by a succession of columns in each photo

strengthening the aspect of continuity in the film and the architecture.

There is an uninterrupted connection between subject, enclosure, event

and plot in each shot. There is also an uninterrupted connection between

the regulated rhythms of the arches and the regulated rhythm of the body

as he vomits. The regulated sound ‘thud’ by the tall open

columns in the rectilinear corridor an they reach the ground and the thud

of Stourely’s body when he hits the car roof.

The roof

structures above his head, weather rounded or flat join the corridors

to the larger buildings and the setting link the events to a bigger picture.

Th seeming endlessness of the corridors, the seeming endlessness of Stourely’s

obsession with stomachs, all events and spaces or setting melding to form

unity.

Therefor

continuity in the architecture has been achieved through rhythm, succession

of columns and spaces, design, materiality and style. While the scripts

or scenarios, story, or dialogue are unified through acts, postures, costumes,

style and demeanors demonstrating continuity in the plot. The architecture

and themes and moments in the film work hand in hand indetermanently and

continuously. Themes persist architecturally and thematically, form unions,

rereveal themselves and reoccur throughout an uninterrupted duration,

without any essential change, strengthening the aspect of continuity within

the film by means of setting or plot. The element of architectural combined

with framing and continuity defines shapes the film, while developing

and unfolding along side Stourely enhancing and describing the trials

and tribulations of his battle with cancer and failed interpersonal relationships.

In themselves, these elements define and describe an era of architecture,

an outlook and philosophy prevalent in the past and present Roman culture

appropriately adopted for an art film of this nature, characterized by

its brutality and exploration into the darker realm of social dynamics,

interpersonal relationships and obsession.

|

|

| |

8. Christian

Tognela

+ Krejcik, Andrea -- use of

colour and photographic images |

|

| |

Christian

Tognela -- A Walk Through...The Belly of an Architect

| B

is for BLACK |

All

the people at the opening of the exhibition are dressed in black,

all but Kracklite’s wife who is in white. All people wear black

suits as if they were at a funeral, and in that moment Kracklite jumps

off the window and falls dead on the car roof. At the same time the

baby is born. In many frames we can see Kracklite in black and his

wife in white...in their belly they are carrying death and life. |

C

is for COLOURS |

They

play a big role, those which appear in every single frame and those

which don’t appear at all. Greenaway used to talk about himself

as a painter who uses film instead of a paintbrush. Red, green, blue,

white and black: everything seems to turn around these pure entities.

F is for FILM Kracklite discovers photos on a wall. Photos of him

while he was not supposed to be portrayed. His life was on these films.

Frames by frames photos seems to reveal what Kracklite could not see. |

G

is for GREEN |

The

colour of evil, the colour that Boullèe hated. The First time

Kracklite feels sick just after having eating green pears; when he

suspects he’s been poisoned by his wife, he’s eating green

figs; Caspasian’s car where he falls onto when he kills himself

jumping off the window is green; light of the copier when he starts

being obsessed by images is green |

K

is for KRACKLITE |

About

colours...could it be possible to split Kracklite into 2 parts? Krack

is to crack...and lite is light..in other words...to break light,

divide light into all its components, analyzing its spectrum and then

choosing the colours...that is what he does. |

P

is for POSTCARDS |

Again

pictures, postcards, photos of momuments. Kracklite writes to Boullèe

about something he cannot handle very well. Can they reveal the truth

to him? |

R

is for RED |

It’

is THE colour. Clothes are red, Kracklite’s clothes are almost

red, when he is at the Pantheon for the first dinner; while watching

copies of belly; everything at the exhibition is written in red; the

ribbon which seems to connect the photos and the life of Kracklite

is red; the main colours of Kracklite’s house is red; the sofa

where he has sex with Flavia is red; red is the chair where he watches

his wife betraying him...all pivotal moments pass through red. |

W

is for WHITE |

The

colour of Boullée’s architecture. The colour of the monument

of the Unknown Soldier in Rome where they want to organize the exhibition. |

X

is for XEROX |

Images

that become obsessions; by the copier it seems that this obsession

increases in intensity, the more he gets copies the more he feels

bad. And on these copies he tries to see his pain. |

Y

is for YANKEES |

The relationships between Kracklite ( the American) and the promoters

of the exhibition ( the Italians) are conflictual. When Caspasian

is asked what he thinks Kracklite is thinking, he answers he’s

American and cannot think. All relationships are wicked, each time

there is some kind of contact it is for money or for blurred issues.

Greenaway as usual is much more interested in the most twisted aspects

of life...what we see is a very greenaway baroque way of describing

things...

|

Andrea

Krejcik: Question: Colour and photography in Belly of an Architect. Using

these aspects in the film, describe your experience of Rome based on the

fact that you have never been there?

Set in Rome,

the movie, Belly of an Architect, is a film showcasing the beauty of Rome

in very distinct and purposeful ways. Colour is used greatly in order

to convey a message to the viewer. It not only enhances and brings contrast

to the scenic images laid throughout the film, but it also sharpens the

main points of the plot. Photography is another medium used with significance

throughout Belly of an Architect to provoke and capture ideas within the

viewer’s eyes.

The prominent colours and shades used throughout the film are red, green,

white, and black. They appear in scenes signifying important moments or

characteristics. Red is most obviously noticed. The colour red has a meaning

of passion, love, warmth and intensity. It also brings an image of blood

or sickness. Stourley Kracklite is seen in many scenes wearing red or

being very near to red objects. Stourley, is an architect who is very

passionate about his work on Etienne-Louis Boullee. However, tragically

he becomes ill which is the cause of his downfall and the loss of his

work. The colour red accentuates his passion during scenes, or identifies

the demise of something close to him. His wife wears red at an opening

function, and later in the film she decides to cheat on Stourley, hence

leaving him for another man. Stourley wears a red tie when explaining

his work, and later his work is taken away from him. This is seen again

as red scaffolding during the construction of his exhibit which will later

be taken away from him. Red is used to show Stouley’s progressing

physical and mental sickness as well. Stouley believes his stomach pains

are brought on by his wife poisoning him. At night when he accuses her,

she is wearing a red night gown. Or the table where Stourley and his companions

sit for lunch is draped with a red table cloth. Again he thinks that someone

is trying to poison him.

Green is a colour more of hope, freshness and nature. In the movie it

is usually shown coming from an unnatural source, which may indicate that

Rome is an older city which must import from other places in order to

bring things of new into the city.

One could argue that being outside, one is still standing inside a structure

in Rome for ruins lay everywhere. The movie indicates such a feeling by

the immense use of whites, greys and blacks. A lot of the scenery is either

concrete or stone and hence takes on a grey hue. This could also mean

however that Rome is pure, which is represented in its white shades. A

colour brought into the city is brought in by foreigners inhabiting Rome.

Therefore green and red are able to stand out so much in the film.

Photography in Belly of an Architect is always shown as black and white.

Black and white can capture the purest of objects. Since Rome and occasionally

Stourley is seen as pure (when he wears white suits during meetings with

exhibit endorsers), colour is seen only when an exterior force is brought

in. On the black and white pictures of a statue’s stomach, colour

is added to the complete or perfect picture only when Stourley tries to

identify his illness. Red is shown as well in the scaffolding which signifies

an alien object for a pure and functioning structure.

The image of Rome using colour and photographic luminaries is one of distinction

through age, and one of purity. Colour along with photography help to

separate, contrast and isolate major artifacts in the city along with

major points in the film.

|

|

| |

9. Federica

Martella

+ Liu, Vivien -- symbolism |

|

| |

Federica

Martella

“The

Belly of An Architect” includes themes as aesthetics of Art and

Architecture, the limits and possibilities of mortality and immortality,

and the influence of obsession and omens. As in all of Greenaway's films,

symbolism, parallelism, allegory, and striking but static visual compositions

are the order of the day.

Many of these symbolic elements are evident in the structure of the film.

First of all it is based on two specific numbers: 7 and 9. The first is

an important number for Rome: it represents the hills of the city, the

kings, the historical periods of the roman architecture. Seven are then

the architectures in Rome that would have impressed Étienne Louis

Boullée's work:

Augustus’s Mausoleum, Pantheon, Colosseum, Villa Adriana, San Peter’s

Basilica, Foro Romano, Piazza Navona and the 'square Colosseum', Palazzo

della Civiltà del Lavoro. Seven are also the postcards that Kracklite

writes to his architect Étienne Louis Boullée.

Number 9 matches instead with the months necessary for preparing the exhibition

on Boullée’s work; with the length of Kracklite’s wife’s

pregnancy, from the conceiving at the beginning of the movie to the born

of Kracklite’s son at the end of it. The movie was made in nine

months as well.

The first

image selected from the film shows Kracklite standing at the top of the

stairs inside the Vittoriano, the monument of Victor Emanuel.

He wears a white suit, creating a contrast with the other characters (white/red,

white/black are the predominant colours contrasts); the symmetry of the

image is evident and he will assume the same Christ-like posture when

he will end his life by falling backwards through the same window, in

the same place, during the opening of his Boullée project. Furthermore,

it is in this moment of the plot when the two Italian men standing beside

him tell him that the architect of the Vittoriano, Sacconi, suicides himself.

This first sequence shows the greatness of roman architecture, underlined

by the Greenaway's outtakes that present a Rome never seen before, frozen

in its eternal beauty and opposed to Kracklite's decline due to his illness.

Then it is inside this place that Kracklite's illness, the pregnancy of

Louisa and the planning for Étienne Louis Boullée's exhibition

end at the same moment: Kracklite dies, Louisa gives birth to her child

and the exhibition is inaugurated.

The pictures on the wall, shown in the second selected sequence of the

film, let Kracklite become aware of what is happening around him and he

understands the weakness and the failure of his life.

“Like

the contours of the body of an organism, whose genetic resources include

the limits within which his growth will be contained, so in the elements

that constitute the structure of the culture are included the limits of

its ‘wholeness’. Every architectural structure has the tendency

to ‘grow’ up till becoming a whole” (J. Lotman, 1998).

Vivien Liu

Greenaway,

in his “The Belly of an Architect”, focuses less on storyline

but rather emphasizes the poetic qualities of Rome’s splendid architecture.

As a viewer who has not experienced in real life the grandeur of Rome’s

architectural treasures, the film provides a poignant introduction through

not only the use of visual communication but also through a mesmerizing

musical score. The major spaces of the Vittoriano have especially been

familiarized to the viewers as many scenes take place within the same

spaces in the building, both in the interior and on the exterior. This

signifies the eternal existence of Rome’s architecture – the

events within them are ephemeral, while the form retains its splendor

and remains constant.

The first

image depicts Kracklite standing in a posture reminiscent of Christ in

front of a window in the Vittoriano – it bears a symbolic meaning

of a heroic death. This becomes clear at the end of the film when the

scene is repeated as Kracklite ends his life by falling through the window

in the same posture. At the same time, his exhibition dedicated to his

hero Boullee is completed, and his wife gives birth to his child. Kracklite’s

white outfit contrasts with the black suits of other men, and creates

a sense of holiness together with his Christ-like posture.

The second

image is when Kracklite discovers the secret documentary of photographs

taken by Flavia, and places himself at the end as part of the sequence.

The series of photographs document the nine months during Kracklite’s

stay in Rome, recalling some painful moments of his failure. He stands

helplessly at the end of the sequence juxtaposed with a picture of his

belly, signifying his obsession and the cause of his downfall.

Boullee’s

dome that was first introduced in the form of a cake at the beginning

of the film is symbolic of Kracklite’s obsession with the oval,

reflecting his obsession with his belly, the pregnancy of his wife, and

Boullee himself, who also suffered a stomach illness. |

|

| |

10. Arvai,

James

How would this film have to be refigured if it were

set in Paris (if you are not familiar with Paris, pick

another urban city other than those already assigned, preferably one with

a rich historic architectural heritage -- but the question will really

not work as well if you don't pick Paris...)? What architectural elements

would you substitute? How would it potentially impact the plot -- ie.

the theme of Boullee?

|

|

| |

In the symbol

rich film “The Belly of an Architect” the artifactual histrionic

architecture of Rome plays a central role. Various monuments of the Roman

Empire are displayed as static symmetrical images for some 10 to 20 seconds

as a powerful visual metaphor for Rome’s endurance and scale. It is

a counterpoint to the limited time-scale of the individual. The individual

architect, Kracklite, with his obsessions, suspicions, delusions, and paranoia

faces the truth of his incomplete life and pending death against the backdrop

of the constancy of Rome’s monuments.

In Paris,

as in Rome, Kracklite would be the ineffectual foreigner floundering in

a strong traditional closed culture.

If the film

were to be transplanted to Paris, architectural monuments would have to

be selected that maintained the same metaphorical relationship of enduring

monument to fragile man. The monuments would have to speak to the apex

of French classicism, when Paris was the center of western civilization,

the 19th century.

The welcoming

dinner scene set in the piazza in front of the Pantheon could be reset

with diner in the park in front of the Eiffel Tower – a monument

of permanence built in 1889 commemorating the centenary of the French

Revolution, a pivotal moment in the 18th century. Kracklite could be shown

visiting Napoleons Tomb as a substitute to Augustas’s mausoleum.

The Piazza Navone could be replaced by the Champs D’elysee. The

Palace of Versailles as the Baroque monument of France could be substituted

for the Coliseum and Hadrian’s Villa. The exhibition venue location

at the monument to Victor Emmanuel II could be substituted with the Louvre

as the architectural monument to French cultural achievements.

The theme

of Boullee as a clever transcending image could stay intact in this Parisian

setting. Boullee’s fifteen minutes of fame for the belly-like spherical

Cenotaph for Isaac Newton is juxtaposed against the belly of the architect.

Boullee, who’s Cenotaph was never built, seems a perfect fit to

Kracklite’s incomplete life and inability to control events in his

life. Kracklite also wonders if Boullee, an outsider, was caught up in

the futility of a foreigner finding himself swept under in a culture of

tradition that is stronger than the strengths of an individual.

Kracklite,

in Paris, could have obsessed on Boullee, French Kings and Baroque landmarks.

Kracklite

could have self-destructed in Paris as well as in Rome.

|

|

| |

11. Nelson,

Aaron

How would this film have to be refigured if it were

set in Dublin? What architectural elements would you

substitute? How would it potentially impact the plot -- ie. the theme

of Boullee? |

|

| |

Keeping

the theme of Boulee and refiguring and placing the movie The Belly of an

Architect in Belfast, leaves and creates many cultural impacts on the story

line while preserving the original plot. The story would read as such:

The movie would open with the couple making their way on train from southern

Ireland to Northern Ireland, The opening dinner party to celebrate the exhibition

of Boullee would be in the gardens in front of Belfast castle situated on

the slopes of Cave Hill over looking the city and the Lough. The exhibition

will be held in the Ulster museum. Stourley would become obsessed with the

troubles and with southern Ireland, which is fueled by his stomach pains

and desire to become involved. His paranoid lack of interest in his wife

leads to her affair with a charming young Irish architect, bringing pregnancy.

Stourley further obsession of the troubles brings self portraits and photographs

of himself in Republican solder attire, constantly focusing on his stomach.

His obsession leads to him loosing the contract to direct the Exhibition

at the Ulster museum due to his political connections. Instead of walking

through the roman busts Stourley will be driven in an RUC land rover through

and around the dangerous areas of Belfast being shown how supporters have

met their end, and a warning to leave the country or you might meet the

same ends. The ending of the exhibition shows his wife pregnant cutting

the ribbon alone. Stourlely lies dead outside the museum after being shot

due to his involvement in the troubles.

The scenes of him eating an orange in the roman ruins would be replaced

with an apple, walking through the glens of Antrim, and swimming in the

Lough, and the first meeting of his wife's adulterer would take place at

the neo-Romanesque architecture of St. Anne's Cathedral. |

|

| |

12. Myers,

Elizabeth

How would this film have to be refigured if it were

set in New York (if you are not familiar with New York,

pick another urban city other than those already assigned)? What architectural

elements would you substitute? How would it potentially impact the plot

-- ie. the theme of Boullee?

|

|

| |

The Belly

of an Architect is a beautiful film, full of the sites, sounds and experience

of Rome. To imagine it taking place in New York instead would be to completely

change the film. Unlike many films that could be set anywhere, The Belly

of an Architect is as much about Rome as it is about the plot itself.

Setting wise,

the many picturesque shots of picnicking out of doors by the base of a

monument or over looking the number of notable buildings would most likely

be eliminated. To dine in New York means to experience one of the many

wonderful restaurants. It is about the interior, the small scale, the

chef and the décor. There are few places where one would want to

picnic on the streets of Manhattan. This would mean that the intimate

feeling of the film would be loss. Instead of private gatherings in quiet

places, they would be meeting in busy restaurants or bars, surrounded

by other activities and conversations. The sounds of the film would change

from the peace of church bells to traffic, sirens and the constant murmuring

of other people. Most notably, the entire pace of the film would be speed

up. Instead of leisurely walking, dinning or conversing, the film would

consist of quick cab rides, and efficient dinning resulting in much less

idol chit chat. The film would take on the speed of New York.

The Belly

of and Architect is constantly emphasizing the many architectural elements

that make up Rome. The film makes a point to include many significant

landmarks in the city. If the film were set in New York they would need

to be substituted with New York’s important icons. I would imagine

The Brooklyn Bridge would be a important image, as well as the Metropolitan

Museum, the plaza at Lincoln Center and Grand Central Station, these all

being important civic spaces could incorporate scenes of gatherings or

of contemplation. The “architectural influences” could come

from buildings such as the Flat Iron building, the brownstones of Brooklyn,

or the early skyscrapers. Time Square might be used as a daily unnoticed

background and Central Park could substitute for the Roman Forum, the

one place of calm and serenity within Manhattan. However these places

would all be very crowed with both locals and tourist, unlike the places

of solitude presented in the film.

Changing

the setting of the film would impact the plot to some degree. Since much

of the plot centers around the relationship between the Italians and the

Americans, this would be lost. However, New Yorkers can also take on an

attitude of superiority to outsiders. The idea of New York as being this

strange, exotic place wouldn’t quite fit for an architect from Chicago.

Therefore the feeling of isolation and helplessness wouldn’t make

sense either. The setting change would mainly impact the underlying themes

throughout the film, ideas of dining, nudity, and peaceful meanderings.

The constant comparison to members of Roman history would be lost, and

difficult to replace. The film would be spead up, and the timelessness

would be lost.

|

|

| |

13. Votruba,

Michael

How would this film have to be refigured if it were

set in Toronto? What architectural elements would you

substitute? How would it potentially impact the plot -- ie. the theme

of Boullee? |

|

| |

Refiguring

the film in Toronto would affect its perception of in a dramatic way. For

example the opening scene we see Stourley Kracklite, his wife, and his other

supporters having a dinner party in front of the Pantheon would be altered

in perception. During this event we see that that space is comfortable for

their dinning party. Now when I think of Toronto and try to imagine eating

in front of one of the city’s significant urban artifacts I cannot

imagine the same feeling of experience. The Pantheon is Rome’s great

dome while Toronto’s is the Sky Dome. When I imagine the public space

surrounding the Sky Dome in Toronto there is not the same sense of locus

as the Pantheon. The event of dinning at such a place would be open to much

speculation from other citizens and would not maintain the same sense of

interiority as in Rome. The dinner party event first introduces Stourley’s

admiration of Boullee; in front of the Sky Dome this would be appropriate

in creating an introduction to Boullee’s obsession with mega structures.

Again if

the film were refigured to take place in Toronto there is not a direct

substitute for Hadrian’s Villa. Perhaps Fort York could be a substitute

here. This change in place would alter the film shifting the experience

of the events that take place. In this change there is contrast between

the finely articulated marble of the villa and the stocky wood buildings

of the fort. The scene that takes place with a lunch gathering within

the ruins at Hadrian’s Villa would be altered in feeling and composition

upon moving it to Toronto. At Fort York a scene with this type of sensuality

is not possible. The scene would need to be filmed having a picnic on

the grassy lawn of the Fort. The scene with Stourley’s wife and

her secret rendezvous would also be difficult to construct here. Perhaps

Stourley could overlook their scene of secret intimacy against a pole

under the Gardiner Expressway. This scene is one that truly aggravates

Stourley’s stomach problems and hence intensifies his relationship

to Boullee.

One of the

most characteristic shots in the film is in front of the National museum

in Rome. If the plot of this film were shifted to Toronto a similar shot

could take place in front of the R.O.M. Here the difference between the

two museums is rather evident. In Rome is symmetry and completion while

with the R.O.M, newly being renovated by Daniel Liebskind, is fragmentary

and incomplete. In his relationship to the Museum perhaps the fragmentary

nature of the R.O.M. could be easier for Stourley to relate to since his

life beginning with his wife’s betrayal has become fragment. The

refiguring would signal the fragmentary nature of Stourley’s life

and his relationship to Boullee thus relating to the original plot.

|

|

| |

14.

A general question for the Italian students. What is your impression of

the conflict in the film as it relates to the representation of the Italians

and their relationship with the Americans?

|

|

| |

Body language

While in

most of movies we can say actors are instructed by director’s hand,

here all the characters are strongly manipulated by director’s hand

and re-presented through his eye.

Under this

point of view Greenway works with stereotypes in a strange manner: on

one side we see excess of Italian cliché, mostly used to underline

certain moments of the movie: Kracklite paying the little Italian to post

his card to Boullee, the fake stroke as promotional event, the missing

founds for the exhibition due to Italian tricks; in other moments American

cliché are used in a reverse way, for example when Kracklite gets

drunk at Pantheon.

But in the

same scenes, if one character is behaving as a cliché, the actor

in front of him is not.

Especially in terms of body language, we receive contradictory messages:

The two ladies at the restaurant look clearly Italian, but act as old

English lady.

Sergio Fantoni,

Kracklite Italian sponsor, has an incredible English style, he never speaks

loud.

Caspasian would be ridiculous if we had to considered him a stereotype

of Italian lover.

What seems to overcome any form of language and communication is money:

what in North America is strictly defined by a written contract is bargained

by a tricky handshake in Italy. Stereotypes of specific countries?

Maybe, but

that’s not the point. The point is that money is acting, as well

as corruption (political, moral, etc.) in terms of metalanguage every

time deep feelings cannot go through.

But this is happening in movies only, isn’t it?

Francesco Mancini

|

|

| |

|

|