Report Prepared by: Matthew Hague, student particicpant at this year's Global Studio from the University of Waterloo, Canada.

During the summer I participated in a program for students called Global Studio.

Global Studio was spearheaded by the United Nations Millennium Project Task Force on Improving the Lives of Slum Dwellers in 2004, and has been developed by various universities. Through participatory design and planning Global Studio addresses the need for design professionals to learn to work effectively with communities experiencing disadvantage or social exclusion, with the overall aim of developing more equitable, sustainable and liveable cities. A key question for Global Studio is how can city building professionals contribute to the implementation of the Millennium Development Goals while contributing and challenging urban theory and practice. Global Studio is an on-going teaching and research project and aims to provide opportunities for new modes of professional education and practice with policy and research implications as well as possibilities for developing networks and partnerships. Global Studio Johannesburg (2007) was preceded by Vancouver (2006) and Global Studio Istanbul (2005).

Johannesburg, in South Africa's Gauteng province, was interestng this year's site for Global Studio because it is a city at the crossroads. The financial capital of South Africa (and in many ways the financial hub of Sub-Saharan Africa) the city is striving to become a major global player . Looking to lead the country forward after the end of Apartheid (only thirteen years ago), Johannesburg is home of the country's Constitutional Court, and will be the host of the 2010 FIFA World Cup. As 2010 approaches major projects are underway, including efforts to ‘green' the public transport system. Yet as is well known many people live in shacks and settlements, there is considerable class inequity, and the scars of apartheid are still prevalent on the urban landscape with distinct boundaries between where the rich live, and where the poor live. Adopting GS' participatory design approach, Global Studio was an interesting opportunity to see what design interventions were possible in three of Johannesburg's poorest communities (Diepsloot, Alexandra Township, and Marshalltown) to better integrate them into the greater Johannesburg context. Projects developed through Global Studio tackled these issues in various ways at vaious scales, ranging from designs that looked at large urban issues to small-scale community issues. This web-site looks at both the over-all Global studio experience, as well as the implimentation of one of the small-scale projects (the project I worked on), Community Blocks.

Global Studio was hosted by the University of the Witwatersrand, University of Sydney, Columbia University, University of Rome, University of Nairobi. Global Studio Johannesburg (GSJ) brought together over 100 students, teachers and practitioners of architecture, planning, landscape architecture, industrial design, community development and international relations from 52 universities and over 20 countries.

Below is the group shot of all the Global Studio participants including mentors and critics (I am in the red circle).

Global Studio officially started on June 30 and ended on July 19, but was preceded by the People Building Better Cities conference. Over four days PBBC profiled best participatory city building professional, educational and research practices in South Africa, Africa and the world, as well as the current and emerging social, political, design and environmental challenges facing the implementation of the Millennium Development Goals. PBBC focused heavily on South African architecture and people's stories, including those of children in the context of migration, urban vulnerability and development. Exploration of issues of exclusion or inclusion on the part of the design professions and educational institutions, and the contribution of participatory planning and design to improving both lives and the environment, was critical to PBBC.

From left to right above: University of the Witwatersrand Campus; a market building in Soweto; a former prison yard; South Africa's new Constitutional Court occupying part of the same former prison yard site).

People Building Better Cities was not only a great opportunity to learn about Jannesburg, but also to see it. The conference was not confined to the classroom (although it was based on the University of the Witwatersrand campus), there were organized excrusions during the day and at night.

In-between PBBC and Global Studio, half of the delegates went to Maputo, Mozambique, and the other half went to Durban, a South African port city on the Indian Ocean. The purpose of the trip was partially to get a broader contextual understanding of the region, but also to relax and have fun before the intensity of Global Study began. Memorable highlights from the trip include visiting the Pheonix Settlement, where Mahatma Ghandi lived when he came to South Africa, and where he published his periodical the 'Indian Opinion,' as well as an amazing sail-boat ride out of Durban Harbour and into the Indian Ocean.

From left to right below: View from the bus of the South African country-side; an intersection in down-town Durban; a successful market and transportation hub; a very windy walk along the long beach, heading to check out the surf competition.

Returning from the trip to Durban, Global Studio officially began. Our home base remained the University of the Witwatersrand campus, where we were all staying in residences, and where we were using the school of architecture's studios. On the first day, all of the students were given overviews of the three potential sites that we could look at over the course of the studio, the three sites (all within the greater Johannesburg area) being Diepsloot, Alexandra Township (a township is an area that under apartheid was designated as a segregated community for non-whites - blacks, coloureds, and working class Indians - usually peripheral to cities or towns, and often under-developed in terms of infrastructure) and Marshalltown. The three sites have very different characteristics: Diepsloot is on the periphery of Johannesburg, and was originally established as a resettlement community to ease the over-population in other township areas (such as Alexandra Township, where people were living dangerously in the flood plane of the Jukskei river, and so were moved to Diepsloot). Alexandra is township with a strong community identity and very proud sense of history (famous former residents include Nelson Mandela), but bursting at the seems with between three-hundred and fifty and five hundred thousand people living on a parcel of land that was originally designated for no more than seventy-thousand people. located near the centre of Johannesburg, Alex sits on the main highway link between Johannesburg and Pretoria, and is adjacent to the wealthy suburd of Sandton, and the industrial hub Wynberg. Marshalltown is in the Central Business District of Johannesburg, and is comprised mainly of warehouse buildings (most of which are vacant) that have been taken over as transitionary housing (an illedal practice known as 'hijacking' the buildings).

From Left to right below: Diepsloot, Alexandra Township, Marshaltown.

The site that I looked at was Alexandra Township (or Alex as it is known to locals). Originally annexed to be farmland, Alex has been a ‘native township' since 1912. Designed to house a population of 70 000 people, the population is currently estimated at between three hundred and fifty thousand to five hundred thousand people. With an area of just one square mile, Alex has some of the highest density housing in South Africa. With people living in a variety of housing, including low-rise hostel buildings, single room shacks, and mid-sized houses, the fabric of Alex ranges from pre-Apartheid British bond housing to self-made informal dwellings to larger (almost suburban) houses that have been made by residents whose financial situations have greatly improved since the end of Apartheid, but who have chosen to stay close to their roots. Below is an aerial view of Alex and its surrounding context (the extents of Alex are in red). Alex is bound on all sides, by an adjacent industrial area of Wynberg to the west and south, a suburb to the north, and the the Jukskei river to the east.

As is evident from the below aerial view, Alex is a place of incredible contrast - a place where the rigidity of the street grid is contrasted by the incredible agglomeration of shack dwellings (which, although it's not visible, have their own internal street and yard network that is incredible experience to walk through, because the passage ways can be quite narrow, but there can be many houses that front onto them) which is contrasted again by the large seem so out of place amongst such incredible density – and then there are the hostel buildings (that are evident on the aerial because of their oblong hexagonal and diamond plan formations), that are so large they even begin to dwarf the soccer fields.

Below: Aerial view of Alex (north is up).

The contrasts are not only evident by looking at the plan view, they continue into the more tangible experience of being in Alex. There are formal stores, places to check e-mail and buy cell phone cards - there are places of employment and social services - there are over one-hundred NGO's working within Alex that are trying to tackle a myriad of issues, from women's rights to HIV/AIDS education and awareness to youth empowerment - there are schools, churches, community centres, and even night clubs. There is also a well developed informal economy, with people selling food and clothing along the main roads. It is hard not to get up in the energy in Alex - it truly feels like a city onto itself – with the streets alive with people, adults and children, many of whom are very friendly, there is a sense that good things are happening in Alex, most of which probably springs from the communities strong sense of history – it has seen and survived the worst of apartheid, has been home to many artists, musicians, and heroes – there are twenty five identified heritage sites in Alex that commemorate people and places instrumental in the struggle against Apartheid. The extreme poverty, however, is undeniable - unemployment is estimated at well over fifty percent, and although it is hard not to spot the odd BMW parked in a well maintained yard, in front of a newly finished house, it would be fallacious to overlook the fact that most of the people living in Alex live below the poverty line.

Above from left to right: A view up a main street towards the low-rise hostels in the distance; Tenth Avenue street sign; informal houses off a main street (suilt right up to the road, with no sidewalk), inside the Sankopano Community Centre).

Below near from left to right: A dry cleaner and convenience store on a busy main street; a large soccer pitch; dancing in a large church yard.

Below far from left to right: Children playing on their own soccer field; women selling vegetables on the side of the road; an innovative window detail.

My initial visit to Alex was overwhelming - the sites and smells and activity and energy and contrasts and changes from block to block were just so much to take in. The first site visit was conducted by one of the studio co-ordinators, Peter Rich, who, as a local architect, has completed an innovative collaborative design project with local residents called the Nelson Mandela Interpretation Centre (a heritage center as well as restaurant, community space, and retail centre). Equally instrumental in helping with the first, as well as many site visits afterwards, was Thabo Mopasi, a community member who tirelessly helped all of the students find the resources, contacts, and places they were looking for. The purpose of the visit was to become familiar with the space, because afterwards the group of students looking at the site (thirty in total) were asked to split into groups based on interest. I worked in the Youth and Culture group, and together with Jenna Stelli (Architecture student from Johannesburg, South Africa), Louise Cheetham (Landscape Architecture Student from Pretoria, South Africa), and Katie Fincher (Architecture Student from Sydney, Australia) helped to develop the Community Blocks project. The other major group focuses were housing, heritage, and large scale urban renewal. As a brief note on the studio process, because it will not be discussed in depth on this page, the project was developed through a combination of site visits, and studio crits/presentations. We would often meet as a group, head to site (in a mini-taxi, which in itself was an incredible experience), make our observations or talk to people, then reconvene at our the studio's at the University of the Witwatersrand campus dicuss our evolving ideas with a mentor, or another group.

Below: View from iside a mini-taxi; Thabo showing us around Alex; a typical crit back at the studio.

Although we were not certain what we wanted our final project to be, through thinking about youth and culture we had two major objectives – we wanted to celebrate the vibrant culture of Alex, and we wanted to actively engage young people in the process. Through our continued site visits as a group, we could not help but observe how incredibly creative the people of Alex were – in the way that they constructed their houses, set up their road-side businesses, used materials, or even made use of spaces that might seem unusable in any other context. Also, one of our earlier site visits was to Mama Afrika , Abangani Enkosini Orphanage (although we called it Mama Portia's, after the women who runs the orhanage) – an orphanage that houses over thirty children, and where many more that live in the community (in child-headed house holds or who are living with relatives) come for food and companionship. We wanted to provide something that engaged (at least some) of the children, and helped them to feel empowered over their own space. It was both refreshing and inspiring to work with the kids at Mama Portia's - they were incredibly receptive, enthusiastic, and energetic.

Below from left to right: A street-side shoe repair stand (made of common concrete blocks); heading to Mams Portia's, with Thabo leading the way; a painted wall.

In the end what we decided to do was create a space within the orphanage that was a collaborative effort between the four of us, and a group of the children(there were approximately twenty-five to thirty kids that participated). The space at the orphanage is extremely limited, so our intervention had to be small, but there are two courtyards that we decided to make a seating arrangement in. As designers who were trying to engerder a participatory process we had to establish the extent of our own interventions into the final product and determine where we would leave sufficient room for meaningful collaborations with the children. As such we limited ourselves to material selection, the media and format used for the design excercises, and the site of the final installation. First however we decided to get to know the children better to see how such a process could work. We organized an exercise for them where we brought papers and markers and play dough, and encouraged them to draw/sculpt. We prompted them by asking them a few simple questions: What makes you happy? What are your favourite places in Alex? What do you want to be when you grow up? The kids responded very enthusiastically, and although tentative at first, drew a lot. The women in charge at Mama Portia's orphanage also responded enthusiastically and encouraged us to come back.

Below near all three: Drawing at Mama Portia's Orphanage.

Below far from left to right: Play dough basketball court; drawings by the children; the kids getting Katie dancing!

Encouraged by the response of children from the preliminary drawing excercise, we decided to repeat the process but this time using the elements that we would use to make the installation at the orphanage. On our previous walks through Alex we noticed the use of 'D' shaped concrete blocks that were particularly interesting. They were used for walls, foundations, seats, tables, flower pots - the stack and lay against each other in an interesting way, and so we decided to use those. Instead of drawing, we wanted the kids to paint on the blocks using weather-proof pain. Siting the activity on a large open space just on the other side of the Jukskei river in a park adjacent to a boardering suburb (about a five minute walk from the orphanage - we needed the extra space to spread out and paint) we primed the blocks (with the help of some children that just happened to walk by and ask if they could jump in). Then we arranged the blocks so that the kids from Mama Portia's could paint them (we invited the kids that helped us prime the blocks to stay and paint also). Then, with the help of some of the women from Mama Portia's, we brought the children over and let them loose on the blocks, prompting them with the same questions that we had asked them previously: What makes you happy? What are your favourite places in Alex? What do you want to be when you grow up?

Below near from left to right: The unprimed blocks (called TerraCrete blocks); priming the blocks; the blocks primed and stacked.

Below far from left to right: The blocks arranged for painting, with some fellow Global Studio students helping to arrange them; the kids sitting on the blocks waiting to paint; painting the blocks.

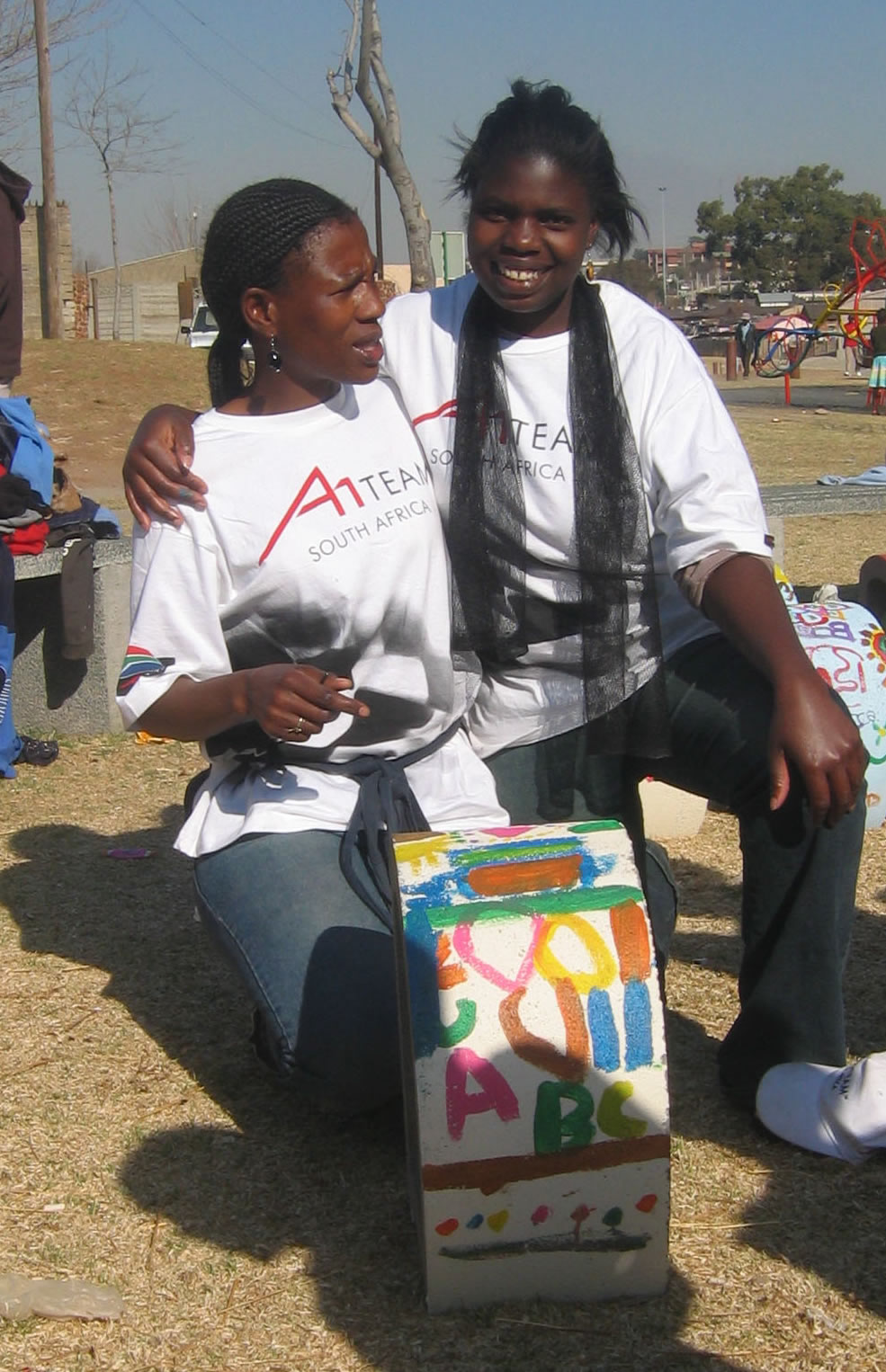

Below from, left to right: After each of the blocks was painted, we took the names of the children that painted it, as well as their photographs, to use in a thank you card that we made later and gave to them before the end of Global Studio; the women from Mama Portia's also painted some blocks - they were really fun.

Below near and far: After the blocks were painted the kids played on them.

Below left right and far: the next day were collected the blocks, and arranged them at Mama Portia's.

Although the project was very small in scale, it was still extremely rewarding, a pleasure to do, and a great learning experience. In particular, it was a great to learn more about the community of Alex by doing a practical, as opposed to a paper, design excercise. Through the Community Blocks project, got a great deal of exposure to the community. Specifically, the Community Blocks project was successful on three points:

1. To celebrate the creative potential of everyday objects.

The D shaped blocks used in the project contribute to the success of this objective: Not only are the blocks used commonly in Alex as a building material for retaining walls, they are also used in a variety of creative adaptations. By using them in the Community Blocks project we further highlighted the blocks as an everyday object worth noticing. In the final product they were used for seating and planters, and in the process they were used as a medium to bring children together to tell each other their stories and express themselves creatively. If the process were to continue, one way to strengthen the success of this objective would be to push the exploration of everyday objects into different areas of study.

2. To meet new communities that we normally wouldn't interact with, learning new ways to communicate and design.

The success of this objective was made by the decision of the design team to engage with the children of Mama Portia's orphanage in the design process. By running the drawing and painting excercises, we learned stories from the children, saw how they communicated themselves through pictures, and developed a greater understanding of the context of their lives in Alex. To enrich the success of this objective, a longer process of design would have to be implemented, including more organized encounters with the children, and a greater reciprocation of stories and experiences. Also, by expanding their inclusion into the design process, enabling them to interact more directly with the decision making process, we could have learned more about the spaces they use, and how they would like to inhabit them.

3. To facilitate the empowerment of children to inform their own spaces.

This objective was achieved by allowing the children to interact one on one with the materials that were ultimately used to inform the installation. Giving children this freedom, hopefully they will feel encouraged in the future to explore other ways in which they can create their own spaces. To enrich this object, as mentioned above, the children would have to be given more liberty to interact and arrange the blocks, to tell us how to place them, or evento place them on their own. Although we did take note of how the children used to blocks as seating and to play games after the blocks were painted, a more in-depth investigation would still be advisable.

It was also a great experience to see another part of the world, and meet other young, interesting students from all over the place. Global Studio was one of those invaluable experiences that only means more and more to me the more I reflect on what I see, who I met, and what I learned.

Report prepared by: Matthew Hague, student particicpant at this year's Global Studio from the University of Waterloo, Canada.