The portrayal of madness has been a staple in dystopic filmmaking since the inception of the medium. One of the earliest examples of such an undertaking can be seen in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. At the beginning of the film, the protagonist, Francis, is situated on a park bench with a friend, and begins recounting a tale from his past. The audience is then transported into his story and thus into a world straight out of an expressionist painting: twisted paths, ceilings that slope irregularly into floors, acutely angled walls, and immutable shadows painted directly onto every surface create a disquieting setting for the murder mystery. When the tale has ended, it is exposed as the sick fantasy of the principle character; Francis is a patient in an insane asylum along with the other characters in the story, except for the evil Dr. Caligari, who, in the narrative uses a trained somnambulist to commit murder, but, in reality, is revealed to be the director of the mental institution. The use of expressionist sets in the film occurs only when we are in the mind of the mental patient, exploiting the controversial new art movement as a way to unnerve the audience and to portray the primary character’s psychological removal from reality, even before we know that he is insane. Viewers are also disturbed by the exposure of Francis as a madman at the end of the film because they have related to and, in a sense, become him throughout the course of the movie, and are now forced to recognize in themselves the ability to confuse reality and fantasy.

Terry Gilliam’s movie, Brazil, is another film in which the lines between reality and fantasy become blurred, and the audience is exposed to an unfamiliar, unsettling view of the world, unsure as to which experiences are real, and which are not. The film follows an office worker who daydreams to escape from the mechanical, bureaucratic society he lives in, until one day he meets the woman he has been dreaming about in person. At this point his dream world collides with his reality, and at times he can no longer differentiate between the two. As the story progresses, Gilliam makes the transition between dream sequence and live action less and less noticeable, until the audience is only guessing which situations are real, which are skewed versions of actual events, and which are merely mental constructs. Near the end he is captured by a secret government agency, as his love for his dream woman and his imagination have made him a risk to their closely monitored society’s way of life, and he is imprisoned and hooked up to a machine that allows his dream world to take over. He believes he has escaped and fled to live happily ever after with his love, but in reality he is still strapped into a chair, being monitored by those who have prevented them from doing just that. The end of Brazil is very similar to that of Caligari because the audience is under the impression that he has escaped his captors, and when he is shown to have never left, they are forced to re-examine what has been real, and what has been imagined.

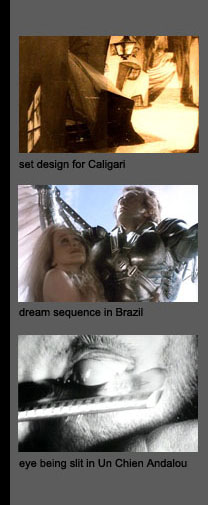

Un Chien Andalou, a French short by Luis Buńuel, takes a quite different approach to the representation of insanity. As the first film intended to disgust rather than entertain its audience, the short makes use of disturbing imagery, including that of an eye being slit with a razor, ants crawling out of a hole in the centre of a mans hand, and a woman poking at a severed limb laying in the street with her walking stick. Presented in a surrealist style, each scene has absolutely no connection with the one preceding or the one following it. Instead of introducing the audience to a character experiencing madness, the film plays upon their sensitivities, equally revolting and disorienting them until they begin to experience a kind of madness themselves. Conflict within or between scenes provokes an emotional, visceral response and appeals to the viewer’s subconscious, creating, at least for the period of time that one is viewing the film, an alternate reality: a ‘surreality’.