The previous four images are examples of how lighting theories observed in paintings or graphic art are subsequently assimilated and transformed in film for dramatic effects that become more complex than simply a graphic or a technicality. The sophistication of storytelling techniques in dystopic films studied in Arch 646 grew as the transformation of these lighting theories were made possible by improvements of artificial lighting and digital tools. “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” and “Sin City” are two examples of the noir genre which directly borrowed from techniques, such as chiaroscuro, indirect lighting, lighting as a composition device and “eye light”, from 17th to 19th century paintings.

Light as a generator of dystopic sensations:

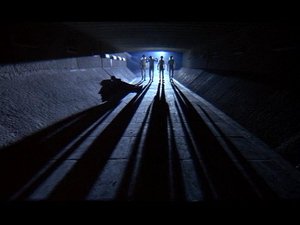

Low-key lighting is derived from the concept of Caravaggio’s Chiaroscuro. The intensity of the key light, the main source of illumination, is much greater than the fill light, which is the light that’s used to soften shadows created by the key lights. The effects can range from a shadowy atmosphere to a high contrast light/dark, which are the two prominent lighting conditions in noir films. Highly intense sources of light were used to create the crisp, and elongated shadows of villains in these films, making them more intimidating for the victims and the audience. Emotional play with light, dark and shadows in the signature low-key lighting of noir films created some of the most beautifully thrilling scenes. Though this was a description of Murnau’s vampire character in Nosferatu, it is equally applicable to mad scientist Rotwang in “Metropolis”, Cesare in “Dr. Caligari”, the cat in “Black Cat”, or Alex and his droogs in “A Clockwork Orange”. Their shadows are “tentacular polyps, translucent, without substance, they are virtual phantoms.” (Victor Stoichita in ‘A Short History of the Shadow’ 1997)