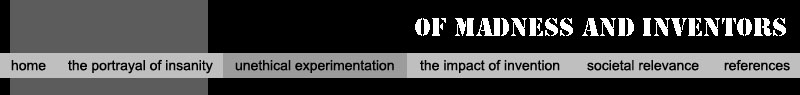

In dystopic film, mad scientists are often shown participating in forms of human experimentation, and usually on subjects who are either unaware of, or opposed to, the procedures. The scientists believe their experiments are justified in that they are worth the cost for some greater good, personal or universal, but the viewer is left wondering what gives them the right to decide what another’s life is worth. The Black Cat is one of the early Holly wood films with such a premise. In the movie, two unsuspecting honeymooners seek shelter in the isolated, modern home of architect Hjalmar Poelzig. Poelzig takes an interest in the young wife, and intends to use her as a sacrifice in one of the satanic rituals that take place in his cellar, where he keeps past victims in suspended animation inside glass coffins so that he may preserve them, and continue to admire their beauty. His scientific experimentation concerning the preservation of his conquests is driven by an intense need to dominate those around him: to take and have what he wants, when he wants it. In this way, he asserts control over his life and the life of others. His scientific inquests have less to do with improving the human condition, and more to do with personal gain.

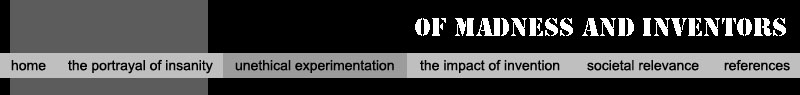

In Stanley Kubrick’s film, A Clockwork Orange, experiments are performed on the movie’s central character, Alex, a juvenile delinquent obsessed with sex and violence. After being caught by police at the house of his latest victim, he confesses to each of the crimes he has committed since leaving correctional school, including rape and murder, and is sentenced to fourteen years in prison. Alex spends several years in prison until he hears of an experimental rehabilitation program that promises to have him released after two weeks of treatment. During treatment he is strapped into a straight jacket and his eyelids are held open so that he is forced to watch violent and sexual acts on screen while drugs induce pain and nausea until the two are psychologically linked and it becomes too painful for Alex to be able commit such crimes. However, when he is released back into the world he is repeatedly attacked by former victims until one uses the classical music from his rehabilitation videos to torture him and he attempts suicide. The government is forced to remove their mental programming. The film brings up moral questions concerning what the life, safety and free will of a criminal are worth compared to the safety of society, and again the audience is made to wonder whether anyone really has the authority to make a decision on the matter. They are also forced to consider if such brutal measures as taken against Alex are worth the end result: do the ends justify the means?

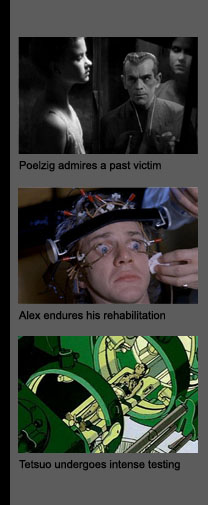

The animated movie, Akira, like Clockwork, also explores the moral issues surrounding the rights of a government compared to the rights of an individual. The action takes place in Neo-Tokyo built next to the ruins of the original city that was destroyed in an explosion that incited the third world war. A member from a teen motorcycle gang, Tetsuo, is taken into government custody and submitted to vigorous testing after coming in contact with a child who has psychokinetic abilities. Tetsuo is found to have strong mental frequencies, on par with that of Akira, whose abilities were the reason behind Tokyo ’s explosion decades ago. The scientists, though ordered to kill him, continue to monitor Tetsuo, and unlock his power, hoping to harness it for military purposes. But he escapes, wreaks havoc on the city, and loses control of his power, instigating a giant explosion that levels the new metropolis, just as Akira had decades before. The ending is typical of Japanese anime; mankind is destroyed in its efforts to play God. The scientists in the film were so preoccupied with the possibilities of harnessing such power that they ignored its potential dangers, not only to the subject of their experimentation, but to the city in its entirety.