Although some movie sets are designed to be benign backdrops to which a film’s events and cast bring life, more compelling are those settings which are characters in their own right. These types of sets are integral to their stories, inciting action, influencing characters, and bringing new depth to the film environment.

One movie that makes use of such integrated set design is Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. The story takes place in the Overlook Hotel, the outside of which is actually the Timberline Lodge Hotel in Oregon, and the inside, constructed of elaborate sets built in Elstree Studios, London, England. The film opens with long aerial shots of a car heading toward the hotel through overwhelming countryside highlighting how separated the Overlook is from the rest of society. The feeling of isolation established here grows steadily throughout the movie as the hotel becomes increasingly snowed-in. This same theme is continued inside when one weighs the vast immensity of the sets against the three tiny occupants; the spaces in the Overlook seem to overpower the characters of the film, exposing them as vulnerable, abandoned and, comparatively, insignificant. This setting supports the narrative, as Jack falls prey to the giant malevolence of the hotel and is driven mad through increasing estrangement from society and his family. The use of symmetry is also prevalent in the set design for The Shining: used to echo the duality present within the story, and also to make anything not a part of that symmetry (for instance, a character or prop) feel out of place. The geometric carpet designs used throughout the film that also play into this symmetry are bright and read almost like optical illusions, giving the viewer the feeling that they might be absorbed into the space. Finally, the frequent use of corridors, and the presence of their outdoor equivalent, the hedge maze, are also key in creating the atmosphere for this movie. These elements give the hotel the feel of a labyrinth, where one never knows what lurks beyond the next corner, and also reference the labyrinth of Greek mythology – an iconography which supports the notion that something sinister is hidden deep within the recesses of the Overlook.

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris is another example of a film where setting is used to further plot and reveal character. Although the motion picture starts at a cottage immersed in nature (used both to establish the nostalgic state of the film’s protagonist, Kris Kelvin, and to create a connection between the audience and the natural world – which they will yearn for later), most of the motion picture’s action takes place aboard a space station orbiting the planet Solaris. Solaris is covered in a vast ocean which appears less like water and more like silver lava, mesmerizing the viewer with its slow, continuous movements. This ocean is viewable from the many circular windows piercing into the space stations outer corridor and those in the occupant’s bedrooms, and, therefore, evokes feelings that it is ever-present throughout the story, although it is not shown much. In fact, its influence is ever-present: entering the minds of those in the station and transforming their innermost feelings of guilt into physical reality. The atmosphere inside the space station is similar to that in The Shining’s Overlook in that it also feels overlarge and appears recently abandoned: thus expressing the film character’s increasing isolation from reality. This cold separation is further amplified using ultra-modern, curved sets which consist of clean white lines or, alternatively, celebrate technology by displaying the ships mechanical systems. And yet, the reality of earth, which they have estranged themselves from, is clearly craved by the Solarists, as they decorate their rooms and labs with reminders of home. This is most recognizable in the space station’s library, where traditional architecture is employed, and the room is filled with books, paintings and photographs of earth. The contrasting settings reflect the conflicting desires of the characters: both to give way to madness, living with those they had believed to be lost, and to return to reality. In another similarity with the set design of The Shining, Solaris makes frequent use of corridors, the spaces in between spaces, which signify that ambiguous area stretching between falsity and reality, good and evil.

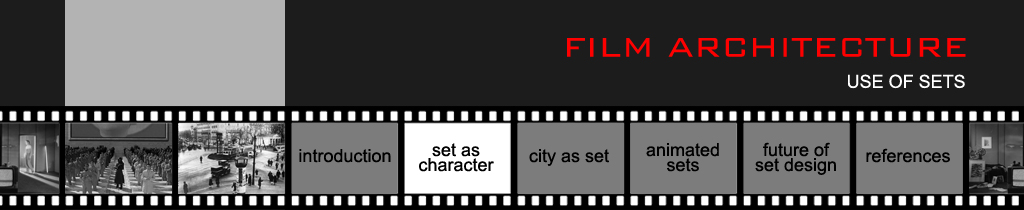

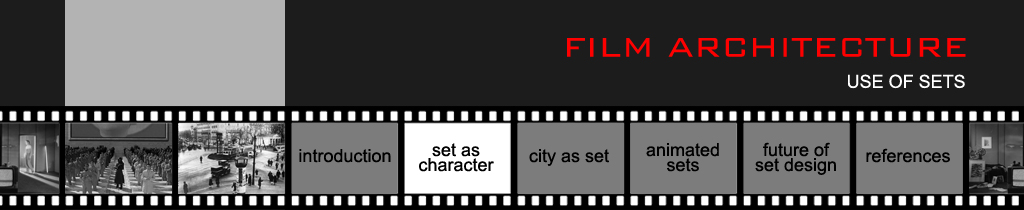

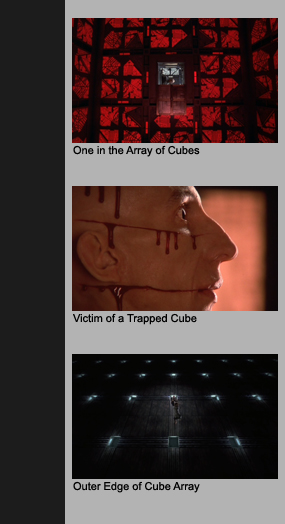

Cube, a film by Vincenzo Natali, is the most direct of this grouping of films in its manipulation of plot and character. Although the entire film was shot in one small cube in which lighting was changed to suggest various colours, the setting revealed in the film is much vaster: a three dimensional array of hundreds of cubes in which seven strangers have been unknowingly imprisoned. The immensity of such a prospect puts emphasis on the helplessness and relative insignificance of the characters. This giant cube of cubes, rather than merely inspiring the characters to violent insanity, though it accomplishes that as well, actually commits murder itself, as various rooms in the array have been set up as traps which use various means to kill their occupants. The plot of the film surrounds the prisoners’ attempts to escape the seemingly endless expanse of cubes, requiring that the characters to get to know each others’ strengths and weaknesses, and work together to solve the massive puzzle. Unfortunately, the environment of fear that claustrophobia, anxiety and isolation creates brings out the worst as well as the best in people, and, although some show amazing strength and humanity, others are driven to violent paranoia. Even the scenes which begin to bridge the gap between the inside and outside of the cube seem only to further separate it from life outside. When the characters struggle to breach the gap separating the inside wall of cubes from the outside, we see only a vast field of openings to more and more cubes, and when Kazan, Leaven and Worth finally make it to the bridge and open the door to the world, we are blinded by light and cannot see anything of the cube’s surroundings. These scenes of hope are thus subverted into scenes of disorientation and desolation.